Offensive Windows IPC Internals 3: ALPC

Contents:

- Introduction

- ALPC Internals

- Putting the pieces together: A Sample Application

- Attack Surface

- Conclusion

- Appendix A: The use of connection and communication ports

- References

Introduction

After talking about two inter-process communication (IPC) protocols that can be uses remotely as well as locally, namely Named Pipes and RPC, with ALPC we’re now looking at a technology that can only be used locally. While RPC stands for Remote Procedure Call, ALPC reads out to Advanced Local Procedure Call, sometimes also referenced as Asynchronous Local Procedure Call. Especially the later reference (asynchronous) is a reference to the days of Windows Vista when ALPC was introduced to replace LPC (Local Procedure Call), which is the predecessor IPC mechanism used until the rise of Windows Vista.

A quick word on LPC

The local procedure call mechanism was introduced with the original Windows NT kernel in 1993-94 as a synchronous inter-process communication facility. Its synchronous nature meant that clients/servers had to wait for a message to dispatched and acted upon before execution could continue. This was one of the main flaws that ALPC was designed to replace and the reason why ALPC is referred to by some as asynchronous LPC.

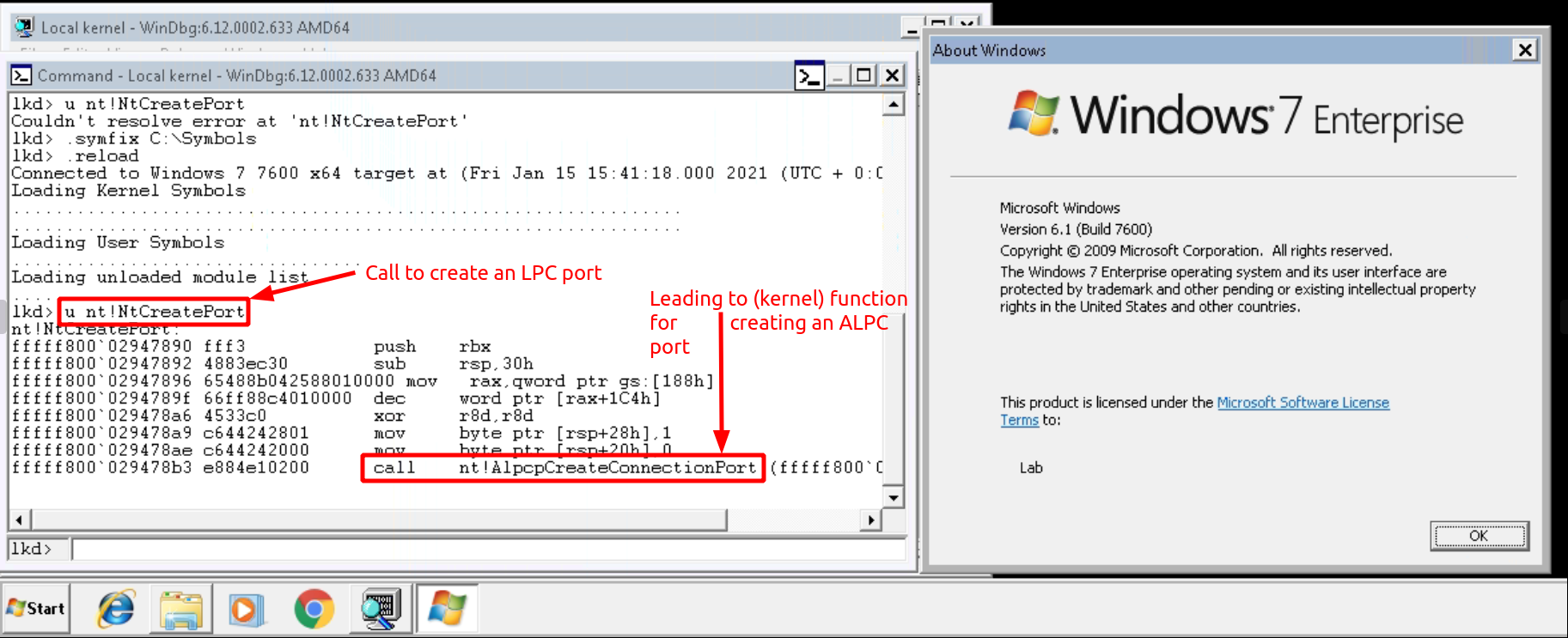

ALPC was brought to light with Windows Vista and at least from Windows 7 onward LPC was completely removed from the NT kernel. To not break legacy applications and allow for backwards compatibility, which Microsoft is (in)famously known for, the function used to create an LPC port was kept, but the function call was redirected to not create an LPC, but an ALPC port.

As LPC is effectively gone since Windows 7, this post will only focus on ALPC, so let’s get back to it.

But, if you’re - like me - enjoy reading old(er) documentations of how things started out and how things used to for work, here’s an article going in some detail about how LPC used to work in Windows NT 3.5: http://web.archive.org/web/20090220111555/http://www.windowsitlibrary.com/Content/356/08/1.html

Back to ALPC

ALPC is a fast, very powerful and within the Windows OS (internally) very extensively used inter-process communication facility, but it’s not intended to be used by developers, because to Microsoft ALPC is an internal IPC facility, which means that ALPC is undocumented and only used as the underlying transportation technology for other, documented and intended-for-developer-usage message transportation protocols, for example RPC.

The fact that ALPC is undocumented (by Microsoft), does however not mean that ALPC is a total blackbox as smart folks like Alex Ionescu have reverse engineered how it works and what components it has. But what it does mean is that you shouldn’t rely on any ALPC behavior for any long-term production usage and even more you really shouldn’t use ALPC directly to build software as there are a lot of non-obvious pitfalls that could cause security or stability problems.

If you feel like you could hear another voice on ALPC after reading this post, I highly recommend listening to Alex’s ALPC talk from SyScan’14 and especially keep an ear open when Alex talks about what steps are necessary to release a mapped view (and that’s only addressing views) from your ALPC server, which gets you at around minute 33 of the talk.

So what I’m saying here is:

ALPC is a very interesting target, but not intended for (non-Microsoft) usage in production development. Also you shouldn’t rely on all the information in this post being or continue to be 100% accurate as ALPC is undocumented.

ALPC Internals

Alright let’s get into some ALPC internals to understand how ALPC works, what moving parts are involved in the communications and how the messages look like to finally get an idea of why ALPC might be an interesting target from an offensive security standpoint.

The Basics

To get off from the ground it should be noted that the primary components of ALPC communications are ALPC port objects. An ALPC port object is a kernel object and its use is similar to the use of a network socket, where a server opens a socket that a client can connect to in order to exchange messages.

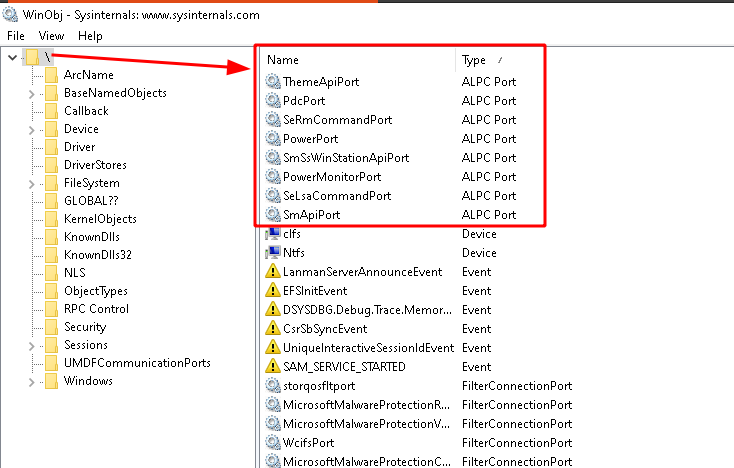

If you fire up WinObj from the Sysinternals Suite, you’ll find that there are many ALPC ports running on every Windows OS, a few can be found under the root path as shown below:

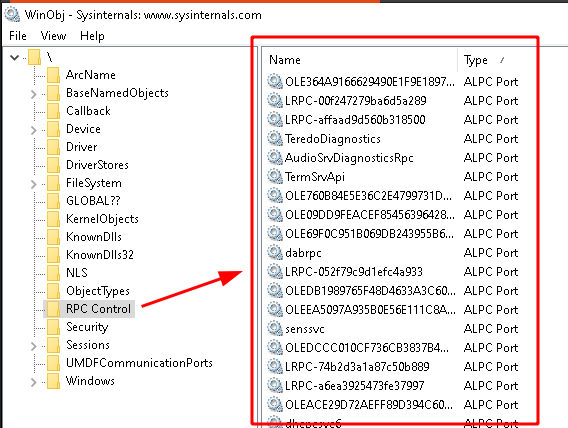

… but the majority of ALPCs port are housed under the ‘RPC Control’ path (remember that RPC uses ALPC under the hood):

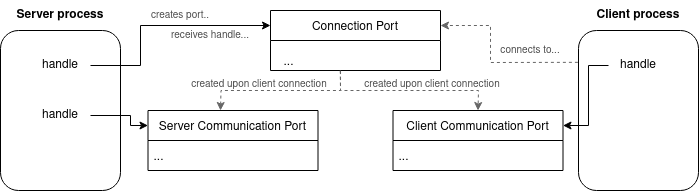

To get started with an ALPC communication, a server opens up an ALPC port that clients can connect to, which is referred to as the ALPC Connection Port, however, that’s not the only ALPC port that is created during an ALPC communication flow (as you’ll see in the next chapter). Another two ALPC ports are created for the client and for the server to pass messages to.

So, the first thing to make a mental note of is:

- There are 3 ALPC ports in total (2 on the server side and 1 on the client side) involved in an ALPC communication.

- The ports you saw in the WinObj screenshot above are ALPC Connection Ports, which are the ones a client can connect to.

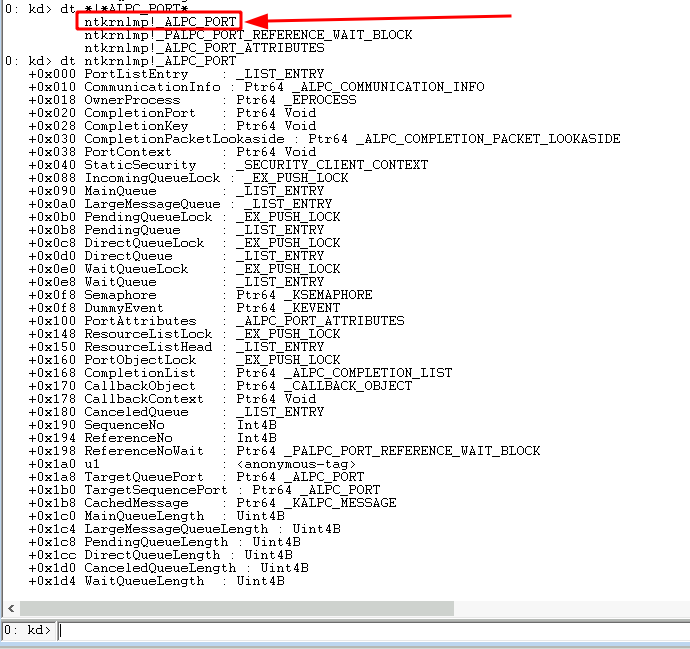

Although there are 3 ALPC ports used in total in an ALPC communication and they all are referred to by different names (such as “ALPC Connection Ports”), there is only a single ALPC port kernel object, which all three ports, used in an ALPC communication, instantiate. The skeleton of this ALPC kernel object looks like this:

As it can be seen above the ALPC kernel object is a quite complex kernel object, referencing various other object types. This makes it an interesting research target, but also leaves some good margin for errors and/or missed attack paths.

ALPC Message Flow

To dig deeper into ALPC we’ll have a look into the ALPC message flow to understand how messages are sent and how these could look like. First of all we’ve already learned that 3 ALPC port objects are involved in an ALPC communication scenario, with the first one being the ALPC connection port that is created by a server process and that clients can connect to (similar to a network socket). Once a client connects to a server’s ALPC connection port, two new ports are created by the kernel called ALPC server communication port and ALPC client communication port.

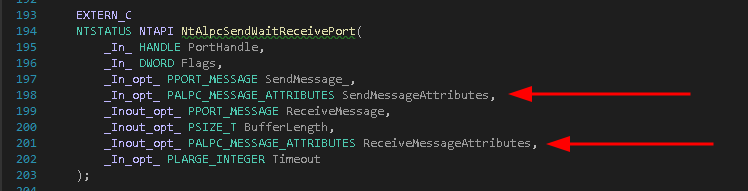

Once the server and client communication ports are established both parties can send messages to each other using the single function NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort exposed by ntdll.dll.

The name of this function sounds like three things at once - Send, Wait and Receive - and that’s exactly what it is. Server and client use this single function to wait for messages, send messages and receive messages on their ALPC port. This sounds unnecessary complex and I can’t tell you for sure why it was build this way, but here’s my guess on it: Remember that ALPC was created as a fast and internal-only communication facility and the communication channel was build around a single kernel object (the ALPC port). Using this 3-way function allows to do multiple operations, e.g. sending and receiving a message, in a single call and thus saves time and reduces user-kernel-land switches. Additionally, this function acts as a single gate into the message exchange process and therefore allows for easier code change and optimizations (ALPC communication is used in a lot of different OS components ranging from kernel drivers to user GUI applications developed by different internal teams). Lastly ALPC is intended as an internal-only IPC mechanism so Microsoft does not need to design it primarily user or 3rd party developer friendly.

Within this single function you also specify what kind of message you want to send (there are different kinds with different implications, we’ll get to that later on) and what other attributes you want to send along with your message (again we’ll get to the things that you can send along with a message later on in chapter ALPC Message Attributes).

So far this sounds pretty straight forward: A server opens a port, a client connects to it, both receive a handle to a communication port and send along messages through the single function NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort… easy.

We’ll on a high level it is that easy, but you surely came here for the details and the title of the post said “internals” so let’s buckle up for a closer look:

- A server process calls NtAlpcCreatePort with a chosen ALPC port name, e.g. ‘CSALPCPort’, and optionally with a SecurityDescriptor to specify who can connect to it.

The kernel creates an ALPC port object and returns a handle this object to the server, this port is referred to as the ALPC Connection Port - The server calls NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort, passing in the handle to its previously created connection port, to wait for client connections

- A client can then call NtAlpcConnectPort with:

- The name of the server’s ALPC port (CSALPCPort)

- (OPTIONALLY) a message for the server (e.g. to send a magic keyword or whatever)

- (OPTIONALLY) the SID of server to ensure the client connects to the intended server

- (OPTIONALLY) message attributes to send along with the client’s connection request

(Message attributes will be detailed in chapter ALPC Message Attributes)

- This connection request is then passed to the server, which calls NtAlpcAcceptConnectPort to accept or reject the client’s connection request.

(Yes, although the function is named NtAlpcAccept… this function can also be used to reject client connections. This functions last parameter is a boolean value that specifies if connection are accepted (if set totrue) or rejected (if set tofalse).

The server can also:- (OPTIONALLY) return a message to the client with the acceptance or denial of the connection request and/or…

- (OPTIONALLY) add message attributes to that message and/or ..

- (OPTIONALLY) allocate a custom structure, for example a unique ID, that is attached to the server’s communication port in order to identify the client

— If the server accepts the connection request, the server and the client each receive a handle to a communication port —

- Client and server can now send and receive messages to/from each other via NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort, where:

- The client listens for and sends new messages to its communication port

- The server listens for and sends new messages to its connection port

- Both the client and the server can specify which message attributes (we’ll get to tht in a bit) they want to receive when listening for new messages

… wait a minute… Why is the server sending/receiving data on the connection port instead of its communication port, since it has a dedicated communication port?… This was one of the many things that puzzled me on ALPC and instead of doing all the heavy lifting reversing work to figure that out myself, I cheated and reached out to Alex Ionescu and simply asked the expert. I put the answer in Appendix A at the end of this post, as I don’t want to drive too far away from the message flow at this point… sorry for the cliff hanger …

Anyhow, looking back at the message flow from above, we can figure that client and server are using various functions calls to create ALPC ports and then sending and receiving messages through the single function NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort. While this contains a fair amount of information about the message flow it’s important to always be aware that server and client do not have a direct peer-to-peer connection, but instead route all messages through the kernel, which is responsible for placing messages on message queues, notifying each party of received messages and other things like validating messages and message attributes. To put that in perspective I’ve added some kernel calls into this picture:

I have to admit on a first glance this is diagram is not super intuitive, but I’ll promise things will get clearer on the way, bear with me.

To get a more complete picture of what ALPC looks like under the hood, we need to dive a little deeper into the implementation bits of ALPC messages, which I’ll cover in the following section.

ALPC Messaging Details

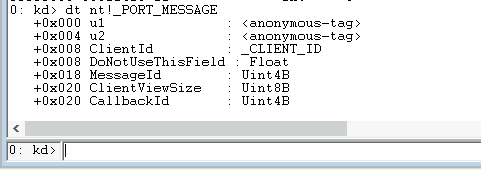

Okay so first of all, let’s clarify the structure of an ALPC message. An ALPC message always consist of a, so called, PORT_HEADER or PORT_MESSAGE, followed by the actual message that you want to send, e.g. some text, binary content, or anything else.

In plain old C++ we can define an ALPC message with the following two structs:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

typedef struct _ALPC_MESSAGE {

PORT_MESSAGE PortHeader;

BYTE PortMessage[100]; // using a byte array of size 100 to store my actual message

} ALPC_MESSAGE, * PALPC_MESSAGE;

typedef struct _PORT_MESSAGE

{

union {

struct {

USHORT DataLength;

USHORT TotalLength;

} s1;

ULONG Length;

} u1;

union {

struct {

USHORT Type;

USHORT DataInfoOffset;

} s2;

ULONG ZeroInit;

} u2;

union {

CLIENT_ID ClientId;

double DoNotUseThisField;

};

ULONG MessageId;

union {

SIZE_T ClientViewSize;

ULONG CallbackId;

};

} PORT_MESSAGE, * PPORT_MESSAGE;

In order to send a message all we have to do is the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

// specify the message struct and fill it with all 0's to get a clear start

ALPC_MESSAGE pmSend, pmReceived;

RtlSecureZeroMemory(&pmSend, sizeof(pmSend));

RtlSecureZeroMemory(&pmReceived, sizeof(pmReceived));

// getting a pointer to my payload (message) byte array

LPVOID lpPortMessage = pmSend->PortMessage;

LPCSTR lpMessage = "Hello World!";

int lMsgLen = strlen(lpMessage);

// copying my message into the message byte array

memmove(lpPortMessage, messageContent, lMsgLen);

// specify the length of the message

pMessage->PortHeader.u1.s1.DataLength = lMsgLen;

// specify the total length of the ALPC message

pMessage->PortHeader.u1.s1.TotalLength = sizeof(PORT_MESSAGE) + lMsgLen;

// Send the ALPC message

NTSTATUS lSuccess = NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort(

hCommunicationPort, // the client's communication port handle

ALPC_MSGFLG_SYNC_REQUEST, // message flags: synchronous message (send & receive message)

(PPORT_MESSAGE)&pmSend, // our ALPC message

NULL, // sending message attributes: we don't need that in the first step

(PPORT_MESSAGE)&pmReceived, // ALPC message buffer to receive a message

&ulReceivedSize, // SIZE_T ulReceivedSize; Size of the received message

NULL, // receiving message attributes: we don't need that in the first step

0 // timeout parameter, we don't want to timeout

);

This code snippet will send an ALPC message with a body of “Hello World!” to a server that we’ve connect to. We specified the message to be synchronous message with the ALPC_MSGFLG_SYNC_REQUEST flag, which means that this call will wait (block) until a message is received on the client’s communication port.

Of course we do not have to wait until a new message comes in, but use the time until then for other tasks (remember ALPC was build to be asynchronous, fast and efficient). To facilitate that ALPC provides three different message types:

- Synchronous request: As mentioned above synchronous messages block until a new message comes in (as a logical result of that one has to specify a receiving ALPC message buffer when calling

NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePortwith a synchronous messages) - Asynchronous request: Asynchronous messages send out your message, but not wait for or act on any received messages.

- Datagram requests: Datagram request are like UDP packets, they don’t expect a reply and therefore the kernel does not block on waiting for a received message when sending a datagram request.

So basically you can choose to send a message that expects a reply or one that does not and when you chose the former you can furthermore chose to wait until the reply comes in or don’t wait and do something else with your valuable CPU time in the meantime. That leaves you with the question of how to receive a reply in case you chose this last option and not wait (asynchronous request) within the NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort function call?

Once again you have 3 options:

- You could use an ALPC completion list, in which case the kernel does not inform you (as the receiver) that new data has been received, but instead simply copies the data into your process memory. It’s up to you (as the receiver) to get aware of this new data being present. This could for example achieved by using a notification event that is shared between you and the ALPC server¹. Once the server signals the event, you know new data has arrived.

¹Taken from Windows Internals, Part 2, 7th Edition. - You could use an I/O completion port, which is a documented synchronization facility.

- You can receive a kernel callback to get replies - but that is only allowed if your process lives in kernel land.

As you have the option to not receive messages directly it is not unlikely that more than one message comes in and waits for being fetched. To handle multiple messages in different states ALPC uses queues to handle and manage high volumes of messages piling up for a server. There are five different queues for messages and to distinguish them I’ll quote directly from chapter 8 of Windows Internals, Part 2, 7th Edition (as there is no better way to put this with these few words):

- Main queue: A message has been sent, and the client is processing it.

- Pending queue: A message has been sent and the caller is waiting for a reply, but the reply has not yet been sent.

- Large message queue: A message has been sent, but the caller’s buffer was to small to receive it. The caller gets another chance to allocate a larger buffer and request the message payload again.

- Canceled queue: A message that was sent to the port but has since then been canceled.

- Direct queue: A message that was sent with a direct event attached.

At this point I’m not going to dive any deeper into message synchronization options and the different queues - I’ve got to make a cut somewhere - however in case someone is interested in finding bugs in these code areas I can highly recommend a look into chapter 8 of the amazing Windows Internals, Part 2, 7th Edition. I learned a lot from this book and can’t praise it enough!

Finally, concerning the messaging details of ALPC, there is a last thing that hasn’t been detailed yet, which is the question of how is a message transported from a client to a server. It has been mentioned what kind of messages can be send, how the structure of a message looks like, what mechanism exist to synchronize and stall messages, but it hasn’t been detailed so far how a message get’s from one process to the other.

You’ve got two options for this:

- Double buffer mechanism: In this approach a message buffer is allocated in the sender’s and receiver’s (virtual) memory space and the message is copied from the sender’s (virtual) memory into the kernel’s (virtual) memory and from there into the receiver’s (virtual) memory. It’s called double buffer, because a buffer, containing the message, is allocated and copied twice (sender -> kernel & kernel -> receiver).

- Section object mechanism: Instead of allocating a buffer to store a message, client and server can also allocate a shared memory section, that can be accessed by both parties, map a view of that section - which basically means to reference a specific area of that allocated section - copy the message into the mapped view and finally send this view as a message attribute (discussed in the following chapter) to the receiver. The receiver can extract a pointer to the same view that the sender used through the view message attribute and read the data from this view.

The main reason for using the ‘section object mechanism’ is to send large messages, as the length of messages send through the ‘double buffer mechanism’ have a hardcoded size limit of 65535 bytes. An error is thrown if this limit is exceeded in a message buffer. The function AlpcMaxAllowedMessageLength() can be used to get the maximum message buffer size, which might change in future versions of Windows.

This ‘double buffer mechanism’ is what was used in the code snippet from above. Looking back a message buffer for the send and the received message has been implicitly allocated via the first three lines of code:

1

2

3

ALPC_MESSAGE pmSend, pmReceived; // these are the message buffers

RtlSecureZeroMemory(&pmSend, sizeof(pmSend));

RtlSecureZeroMemory(&pmReceived, sizeof(pmReceived));

This message buffer has then been passed to the kernel in the call to NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort, which copies the sending buffer into the receiving buffer on the other side.

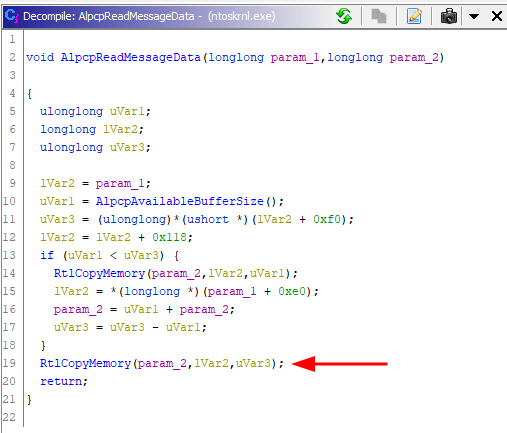

We could also dig into the kernel to figure out how an ALPC message (send via message buffers) actually looks like. Reversing the NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort leads us to the kernel function AlpcpReceiveMessage, which eventually calls - for our code path - into AlpcpReadMessageData, where the copying of the buffer happens.

Side note: If you’re interested in all the reversing details I left out here check out my follow up post: Debugging and Reversing ALPC

At the end of this road you’ll find a simple RtlCopyMemory call - which is just a macro for memcpy - that copies a bunch of bytes from one memory space into another - it’s not as fancy as one might have expected it, but that’s what it is ¯\(ツ)/¯.

To see that in action I’ve put a breakpoint into the AlpcpReadMessageData function shown above for my ALPC server process. The breakpoint is triggered once my ALPC client connects and sends an initial message to the server. The message that the client sends is the: Hello Server. The annotated debug output is shown below:

These debug screens show what an ALPC message send through a message buffer looks like…just bytes in a process memory.

Also note that the above screens is a visual representation of the ‘double buffer mechanism’ in it’s 2nd buffer copy stage, where a message is copied from kernel memory space into the receiver’s process memory space. The copy action from sender to kernel space has not been tracked as the breakpoint was only set for the receiver process.

ALPC Message Attributes

Alright, there’s one last piece that needs to be detailed before putting it all together, which is ALPC message attributes. I’ve mentioned message attributes a few times before, so here is what that means.

When sending and receiving messages, via NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort, client and server can both specify a set of attributes that they would like to send and/or receive. These set of attributes that one wants to send and the set of attributes that one wants to receive are passed to NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort in two extra parameters, shown below:

The idea here is that as sender you can pass on additional information to a receiver and the receiver on the other end can specify what set of attributes he would like to get, meaning that not necessarily all extra information that was send is also exposed to the receiver.

The following message attributes can be send and/or received:

- Security Attribute: The security attribute holds security context information, which for example can be used to impersonate the sender of a message (detailed in the Impersonation section). This information is controlled and validated by the kernel. The structure of this attribute is shown below:

1

2

3

4

5

typedef struct _ALPC_SECURITY_ATTR {

ULONG Flags;

PSECURITY_QUALITY_OF_SERVICE pQOS;

HANDLE ContextHandle;

} ALPC_SECURITY_ATTR, * PALPC_SECURITY_ATTR;

- View Attribute: As described towards the end of the Messaging Details chapter, this attribute can be used to pass over a pointer to a shared memory section, which can be used by the receiving party to read data from this memory section. The structure of this attribute is shown below:

1

2

3

4

5

6

typedef struct _ALPC_DATA_VIEW_ATTR {

ULONG Flags;

HANDLE SectionHandle;

PVOID ViewBase;

SIZE_T ViewSize;

} ALPC_DATA_VIEW_ATTR, * PALPC_DATA_VIEW_ATTR;

- Context Attribute: The context attribute stores pointers to user-specified context structures that have been assigned to a specific client (communication port) or to a specific message. The context structure can be any arbitrary structure, for example a unique number, and is meant to identify a client. The server can extract and reference the port structure to uniquely identify a client that send a message. An example of a port structure I used, can be found here. The kernel will set in the sequence number, message ID and callback ID to enable structured message handling (similar to TCP). This message attribute can always be extracted by the receiver of a message, the sender does not have to specify this and cannot prevent the receiver from accessing this. The structure of this attribute is shown below:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

typedef struct _ALPC_CONTEXT_ATTR {

PVOID PortContext;

PVOID MessageContext;

ULONG Sequence;

ULONG MessageId;

ULONG CallbackId;

} ALPC_CONTEXT_ATTR, * PALPC_CONTEXT_ATTR;

- Handle Attribute: The handle attribute can be used to pass over a handle to a specific object, e.g. to a file. The receiver can use this handle to reference the object, e.g. in a call to ReadFile. The kernel will validate if the passed handle is valid and raise and error otherwise. The structure of this attribute is shown below:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

typedef struct _ALPC_MESSAGE_HANDLE_INFORMATION {

ULONG Index;

ULONG Flags;

ULONG Handle;

ULONG ObjectType;

ACCESS_MASK GrantedAccess;

} ALPC_MESSAGE_HANDLE_INFORMATION, * PALPC_MESSAGE_HANDLE_INFORMATION;

- Token Attribute: The token attribute can be used to pass on limited information about the sender’s token. The structure of this attribute is shown below:

1

2

3

4

5

6

typedef struct _ALPC_TOKEN_ATTR

{

ULONGLONG TokenId;

ULONGLONG AuthenticationId;

ULONGLONG ModifiedId;

} ALPC_TOKEN_ATTR, * PALPC_TOKEN_ATTR;

- Direct Attribute: The direct attribute can be used to associate a created event with a message. The receiver can retrieve the event created by the sender and signal it to let the sender know that the send message was received (especially useful for datagram requests). The structure of this attribute is shown below:

1

2

3

4

typedef struct _ALPC_DIRECT_ATTR

{

HANDLE Event;

} ALPC_DIRECT_ATTR, * PALPC_DIRECT_ATTR;

- Work-On-Behalf-Of Attribute: This attribute can be used to send the work ticket that is associated with the sender. I haven’t played around with this so I can’t go in any more detail. The structure of this attribute is shown below:

1

2

3

4

typedef struct _ALPC_WORK_ON_BEHALF_ATTR

{

ULONGLONG Ticket;

} ALPC_WORK_ON_BEHALF_ATTR, * PALPC_WORK_ON_BEHALF_ATTR;

The message attributes, how these are initialized and send was another thing that puzzled me when coding a sample ALPC server and client. So you don’t crash with the same problems that I had here are secret I learned about ALPC message attributes:

To get started one has to know that the structure for ALPC message attributes is the following:

1

2

3

4

5

typedef struct _ALPC_MESSAGE_ATTRIBUTES

{

ULONG AllocatedAttributes;

ULONG ValidAttributes;

} ALPC_MESSAGE_ATTRIBUTES, * PALPC_MESSAGE_ATTRIBUTES;

Looking at this I initially thought you call the function AlpcInitializeMessageAttribute give it a reference to the above structure and the flag for the message attribute you want to send (all attributes are referenced by a flag value, here’s the list from my code) and the kernel then sets it all up for you. You then put the referenced structure into NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort, repeat the process for every message you want to send and be all done.

That is not the case and seems to be wrong on multiple levels. Only after I found this twitter post from 2020 and rewatched Alex’s SyScan’14 talk once again (I re-watched this at least 20 times during my research) I came to what I currently believe is the right track. Let me first spot the errors in my initial believes before bundling the right course of actions:

- AlpcInitializeMessageAttribute doesn’t do shit for you, it really only clears the

ValidAttributesflag and sets theAllocatedAttributesflag according to your specified message attributes (so no kernel magic filling in data at all).

I’ll have to admit I spotted this early on from reverse engineering the function, but for some time I still hoped it would do some more as the name of the function was so promising. - To actually setup a message attribute properly you have to allocate the corresponding message structure and place it in a buffer after the ALPC_MESSAGE_ATTRIBUTES structure. So this is similar to an ALPC_MESSAGE where the actual message needs to be placed in a buffer after the PORT_MESSAGE structure.

- It’s not the kernel that sets the ValidAttributes attribute for your ALPC_MESSAGE_ATTRIBUTES structure, you have to set this yourself. I figured this out by playing around with the structure and for some time I thought this was just a weird workaround, because why would I need to set the

ValidAttributesfield? As far as I’m concerned my attributes are always valid and shouldn’t it be the kernel’s task to check if they are valid.

I took me another round of Alex’s SyScan’14 talk to understand that.. - You don’t setup the message attributes for every call to NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort, you set all the message attributes up once and use the ValidAttributes flag before calling NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort to specify which of all your set up attributes is valid for this very message you are sending now.

To bundle this into useful knowledge, here’s how sending message attributes does work (in my current understanding):

- First of all you have two buffers: A buffer for message attributes you want to receive (in my code named:

MsgAttrReceived) and a buffer for message attributes you want to send (in my code named:MsgAttrSend). - For the

MsgAttrReceivedbuffer you just have to allocate a buffer that is large enough to hold the ALPC_MESSAGE_ATTRIBUTES structure plus all the message attributes that you want to receive. After allocating this buffer set theAllocatedAttributesattribute to the corresponding attribute(s) flag(s) value. ThisAllocatedAttributesvalue can be changed for every message you receive.

For my sample server and client application I just want to always receive all attributes that the kernel could give me, therefore I set the buffer for the receiving attributes once at the beginning of my code as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

pMsgAttrReceived = alloc_message_attribute(ALPC_MESSAGE_ATTRIBUTE_ALL);

PALPC_MESSAGE_ATTRIBUTES alloc_message_attribute(ULONG ulAttributeFlags) {

NTSTATUS lSuccess;

PALPC_MESSAGE_ATTRIBUTES pAttributeBuffer;

LPVOID lpBuffer;

SIZE_T lpReqBufSize;

SIZE_T ulAllocBufSize;

ulAllocBufSize = AlpcGetHeaderSize(ulAttributeFlags); // required size for specified attribues

lpBuffer = HeapAlloc(GetProcessHeap(), HEAP_ZERO_MEMORY, ulAllocBufSize);

if (GetLastError() != 0) {

wprintf(L"[-] Failed to allocate memory for ALPC Message attributes.\n");

return NULL;

}

pAttributeBuffer = (PALPC_MESSAGE_ATTRIBUTES)lpBuffer;

// using this function to properly set the 'AllocatedAttributes' attribute

lSuccess = AlpcInitializeMessageAttribute(

ulAttributeFlags, // attributes

pAttributeBuffer, // pointer to attributes structure

ulAllocBufSize, // buffer size

&lpReqBufSize

);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(lSuccess)) {

return NULL;

}

else {

//wprintf(L"Success.\n");

return pAttributeBuffer;

}

}

[code]

- For the

MsgAttrSendbuffer two more steps are involved. You have to allocate a buffer that is large enough to hold ALPC_MESSAGE_ATTRIBUTES structure plus all the message attributes that you want to send (just as before). You have to set theAllocatedAttributesattribute (just as before), but then you also have to initialize the message attributes (meaning creating the necessary structures and fill those with valid values) that you want to send and then finally set theValidAttributesattribute. In my code I wanted to send different attributes in different messages so here’s how I did that:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

// Allocate buffer and initialize the specified attributes

pMsgAttrSend = setup_sample_message_attributes(hConnectionPort, hServerSection, ALPC_MESSAGE_SECURITY_ATTRIBUTE | ALPC_MESSAGE_VIEW_ATTRIBUTE | ALPC_MESSAGE_HANDLE_ATTRIBUTE);

// ...

// Before sending a message mark certain attributes as valid, in this case ALPC_MESSAGE_SECURITY_ATTRIBUTE

pMsgAttrSend->ValidAttributes |= ALPC_MESSAGE_SECURITY_ATTRIBUTE

lSuccess = NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort(hConnectionPort, ...)

//...

[code]

- There is an additional catch with the sending attribute buffer: You don’t have to allocate or initialize the context attribute or the token attribute. The kernel will always prepare these attributes and the receiver can always request them.

- If you want to send multiple message attributes you will have a buffer that begins with the ALPC_MESSAGE_ATTRIBUTES followed by initialized structures for all the message attributes that you want.

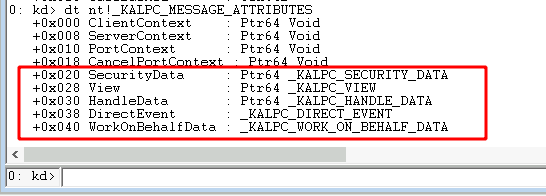

So how does the kernel know which attribute structure is which? The answer: You have to put the message attributes in a pre-defined order, which could be guessed from the value of their message attribute flags (from highest to lowest) or can also be found in the _KALPC_MESSAGE_ATTRIBUTES kernel structure:

- You might have noticed that the context and token attributes are not tracked in this structure and that is because the kernel will always provide these for any message, and hence does track them message independently.

- Once send, the kernel will validate all the message attributes, fill in values (for example sequence numbers) or clear attributes that are invalid before offering these to the receiver.

- Lastly the kernel will copy the attributes that the receiver specified as

AllocatedAttributesinto the receiver’sMsgAttrReceivedbuffer, from where they can be fetched by the receiver.

All of the above might, hopefully, also get a little clearer if you go through my code and match these statements against where and how I used message attributes.

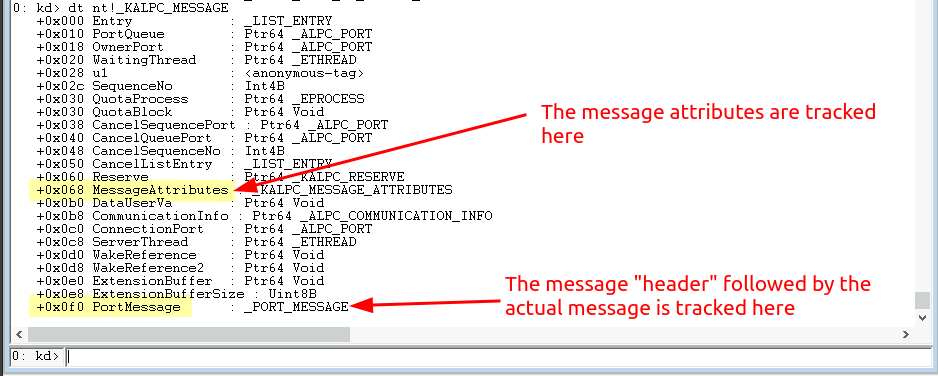

So far we’ve introduced various components of ALPC to describe how the ALPC messaging system works and what an ALPC message looks like. Let me conclude this chapter by putting a few of these components into perspective. The above description and structure of an ALPC message describe what an ALPC message looks like to sender and receiver, but one should be aware that the kernel is adding a lot more information to this message - in fact it takes the provided parts and places them in a much bigger kernel message structure - as you can see below:

So the message here is: We’ve made a good understanding, but there is a lot more under the hood that we’ve not touched.

Putting the pieces together: A Sample Application

I have coded a sample ALPC client and server application as a playground to understand the different ALPC components. Feel free to browse and change the code to get your own feeling for ALPC. A few fair warnings about this code:

- The code is not intended to scale/grow well. The code is intended to be easily readable and guide through the main steps of sending/receiving ALPC messages.

- This code is in absolutely no way even close to being performance, resource, or anything else optimized. It’s for learning.

- I did not bother to take any effort to free buffers, messages or any other resources (which comes with a direct attack path, as described in section Unfreed Message Objects).

Although there aren’t to many files to go through, let me point out a few notable lines of code:

- You can find how I set up sample messages attributes here.

- You can find a call to

NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePortthat both sends and receives a message here. - You can find ALPC port flags, message attribute flags, message and connection flags here.

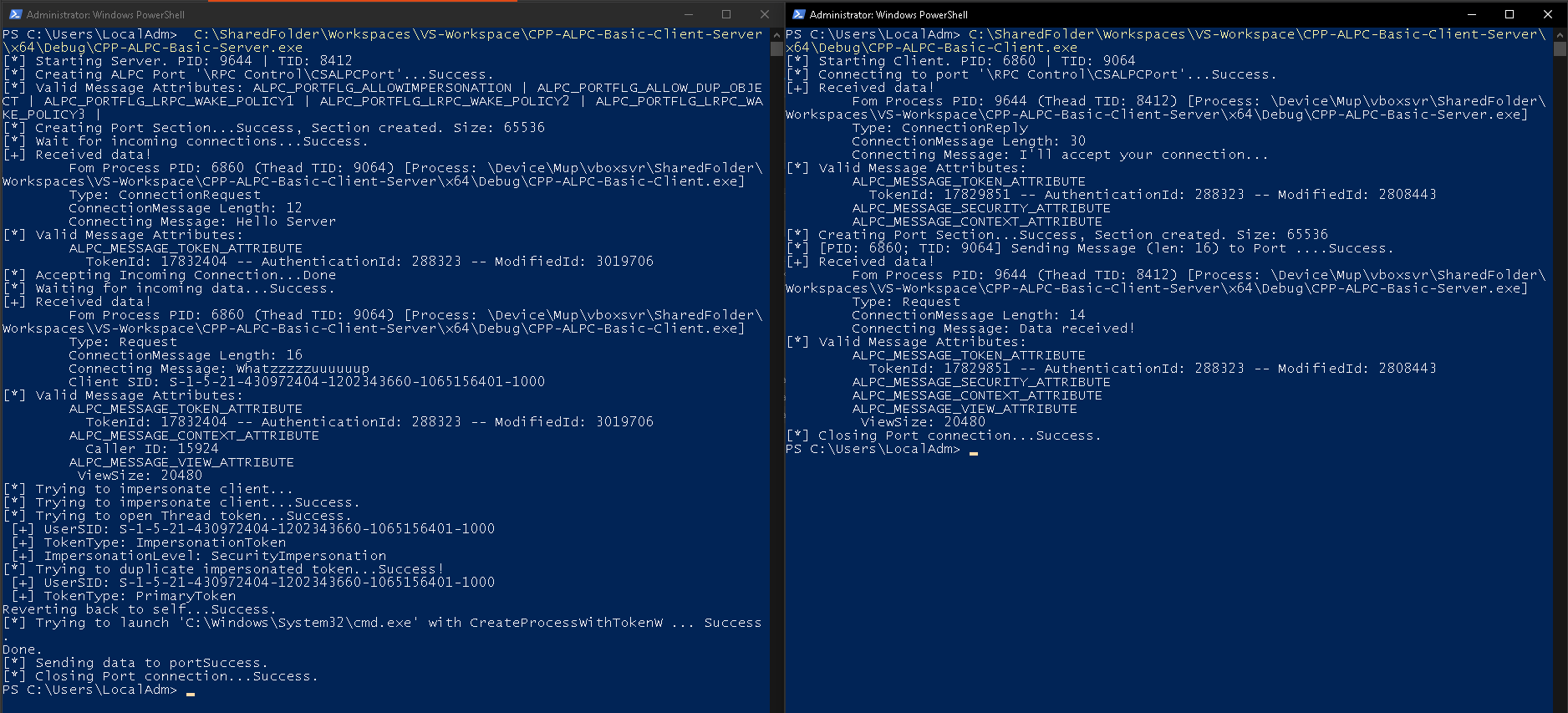

And then finally here is what it looks like:

Attack Surface

Before digging into the attack surface of ALPC communication channels, I’d like to point out an interesting conceptual weakness with ALPC communication that the below attack paths build on and that should be kept in mind to find further exploit potential.

Looking back at the ALPC Message Flow section we can recall, that in order to allow for ALPC communication to occur a server has to open up an ALPC (connection) port, wait for incoming messages and then accept or decline these messages. Although an ALPC port is a securable kernel object and can as such be created with a Security Descriptor that defines who can access and connect to it, most of the time the creating ALPC server process can’t (or want) to limit access based on a callee’s SID. If you can’t (or want) limit access to your ALPC port by a SID, the only option you have is to allow Everyone to connect to your port and make a accept/deny decision after a client has connected and messaged you. That in turn means that a lot of built-in ALPC servers do allow Everyone to connect and send a message to a server. Even if the server rejects a client right away, sending an initial message and some message attributes along with that message, might be enough to exploit a vulnerability.

Due to this communication architecture and the ubiquity of ALPC, exploiting ALPC is also an interesting vector to escape sandboxes.

Identify Targets

The first step in mapping the attack surface is to identify targets, which in our case are ALPC client or server processes.

There are generally three routes that came to my mind of how to identify such processes:

- Identify ALPC port objects and map those to the owning processes

- Inspect processes and determine if ALPC is used within them

- Use Event Tracing for Windows (ETW) to list ALPC events

All of these ways could be interesting, so let’s have a look at them…

Find ALPC port objects

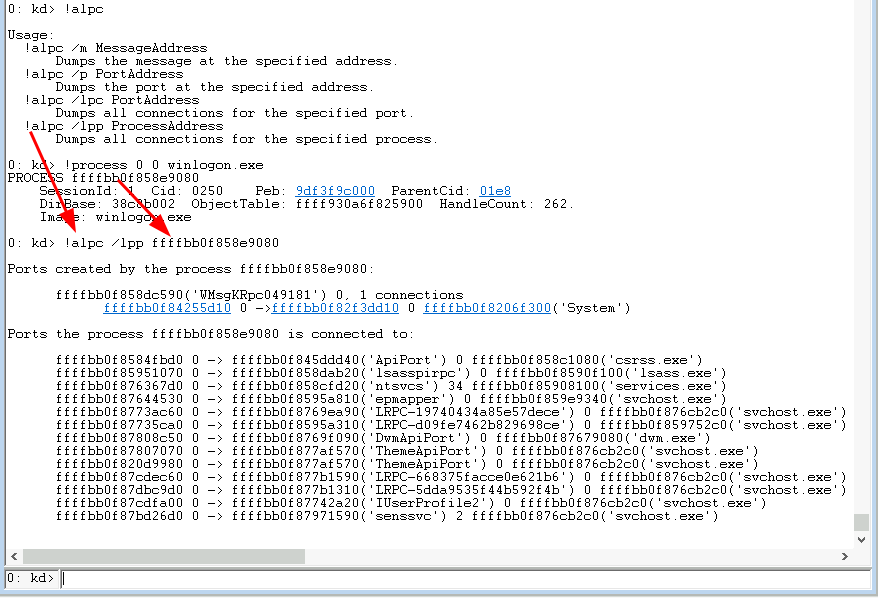

We’ve already seen the most straight forward way to identify ALPC port objects at the beginning of this post, which is to fire up WinObj and spot ALPC objects by the ‘Type’ column. WinObj can’t give us more details so we head over to a WinDbg kernel debugger to inspect this ALPC port object:

In the above commands we used Windbg’s !object command to query the object manager for the named object in the specified path. This implicitly already told us that this ALPC port has to be an ALPC connection port, because communications ports are not named. In turn we can conclude that we can use WinObj only to find ALPC connection ports and through these only ALPC server processes.

Speaking of server processes: As shown above, one can use WinDbg’s undocumented !alpc command to display information about the ALPC port that we just identified. The output includes - alongside with a lot of other useful information, the owning server process of the port, which in this case is svchost.exe.

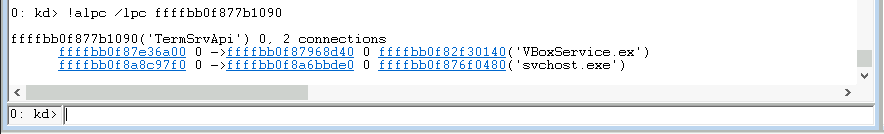

Now that we know the address of the ALPC Port object we can use the !alpc command once again to display the active connections for this ALPC connection port:

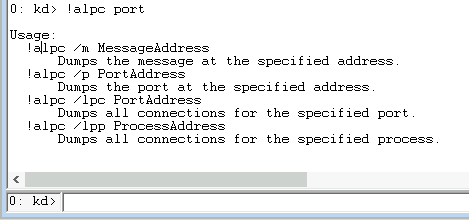

Side note: The !alpc Windbg command is undocumented, but the outdated !lpc command, which existed in the LPC days, is documented here and has a timestamp from December 2021. This documentation page does mention that the !lpc command is outdated and that the !alpc command should be used instead, but the !alpc command syntax and options are completely different. But to be fair the !alpc command syntax is displayed in WinDbg if you enter any invalid !alpc command:

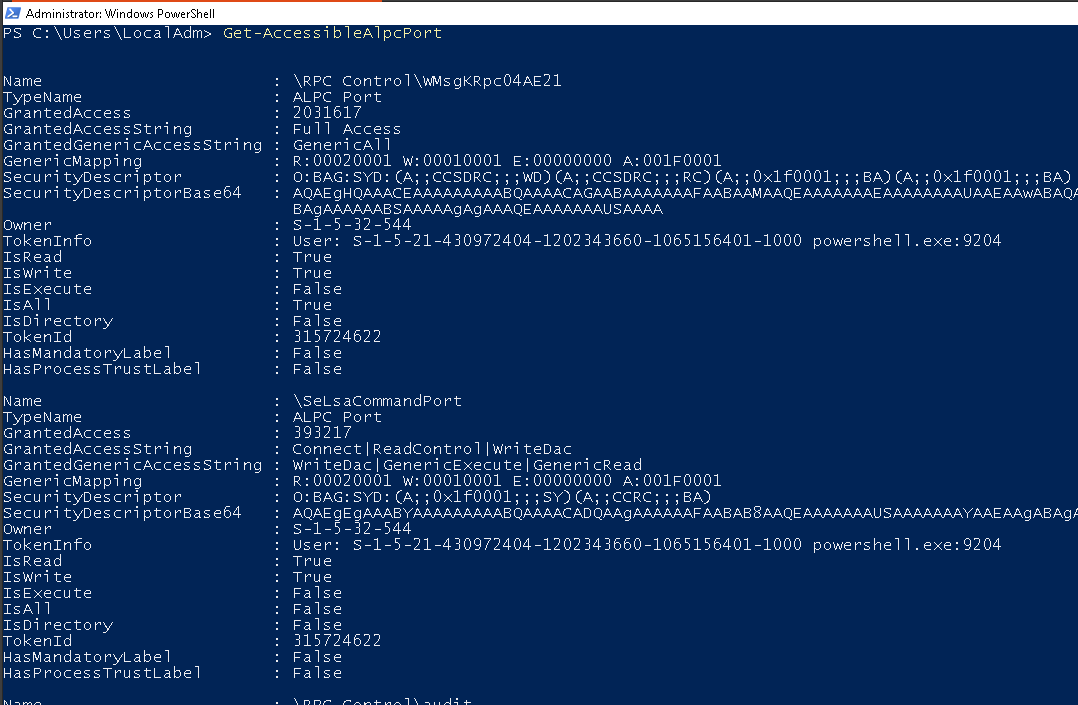

Thanks to James Forshaw and his NtObjectManager in .NET we can also easily query the NtObjectManager in PowerShell to search for ALPC port objects, and even better James already provided the wrapper function for this via Get-AccessibleAlpcPort.

Find ALPC used in processes

As always there are various ways to find ALPC port usage in processes, here are a few that came to mind:

- Similar to approaches in previous posts (here) one could use the dumpbin.exe utility to list imported functions of executables and search therein for ALPC specific function calls.

- As the above approach works with executable files on disk, but not with running processes, one could transfer the method used by dumpbin.exe and parse the Import Address Table (IAT) of running processes to find ALPC specific function calls.

- One could attach to running processes, query the open handles for this process and filter for those handles that point to ALPC ports.

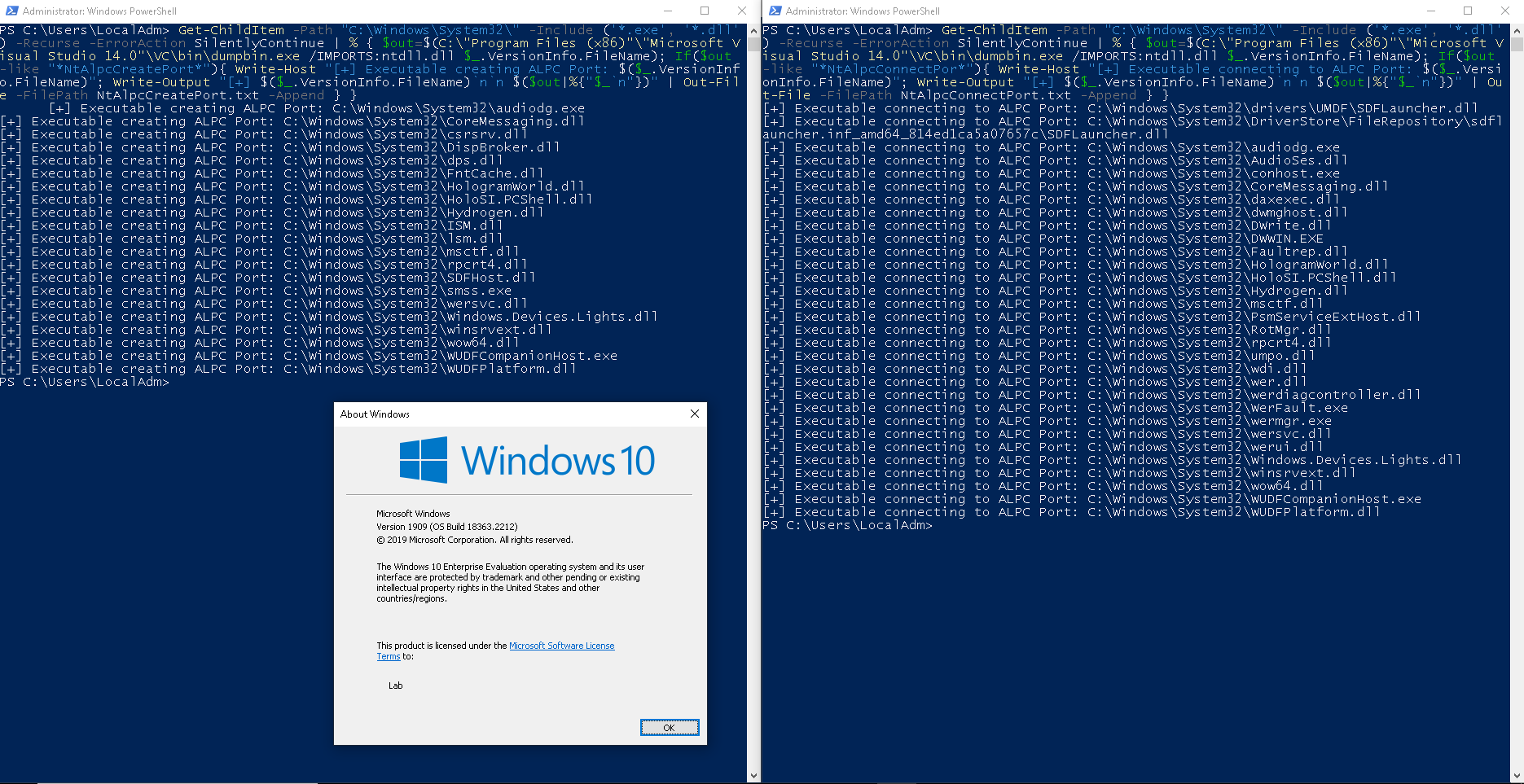

Once dumpbin.exe is installed, which for examples comes with the Visual Studio C++ development suite, the following two PowerShell one-liners could be used to find .exe and .dll files that create or connec to an ALPC port:

1

2

3

4

5

## Get ALPC Server processes (those that create an ALPC port)

Get-ChildItem -Path "C:\Windows\System32\" -Include ('*.exe', '*.dll') -Recurse -ErrorAction SilentlyContinue | % { $out=$(C:\"Program Files (x86)"\"Microsoft Visual Studio 14.0"\VC\bin\dumpbin.exe /IMPORTS:ntdll.dll $_.VersionInfo.FileName); If($out -like "*NtAlpcCreatePort*"){ Write-Host "[+] Executable creating ALPC Port: $($_.VersionInfo.FileName)"; Write-Output "[+] $($_.VersionInfo.FileName)`n`n $($out|%{"$_`n"})" | Out-File -FilePath NtAlpcCreatePort.txt -Append } }

## Get ALPC client processes (those that connect to an ALPC port)

Get-ChildItem -Path "C:\Windows\System32\" -Include ('*.exe', '*.dll') -Recurse -ErrorAction SilentlyContinue | % { $out=$(C:\"Program Files (x86)"\"Microsoft Visual Studio 14.0"\VC\bin\dumpbin.exe /IMPORTS:ntdll.dll $_.VersionInfo.FileName); If($out -like "*NtAlpcConnectPor*"){ Write-Host "[+] Executable connecting to ALPC Port: $($_.VersionInfo.FileName)"; Write-Output "[+] $($_.VersionInfo.FileName)`n`n $($out|%{"$_`n"})" | Out-File -FilePath NtAlpcConnectPort.txt -Append } }

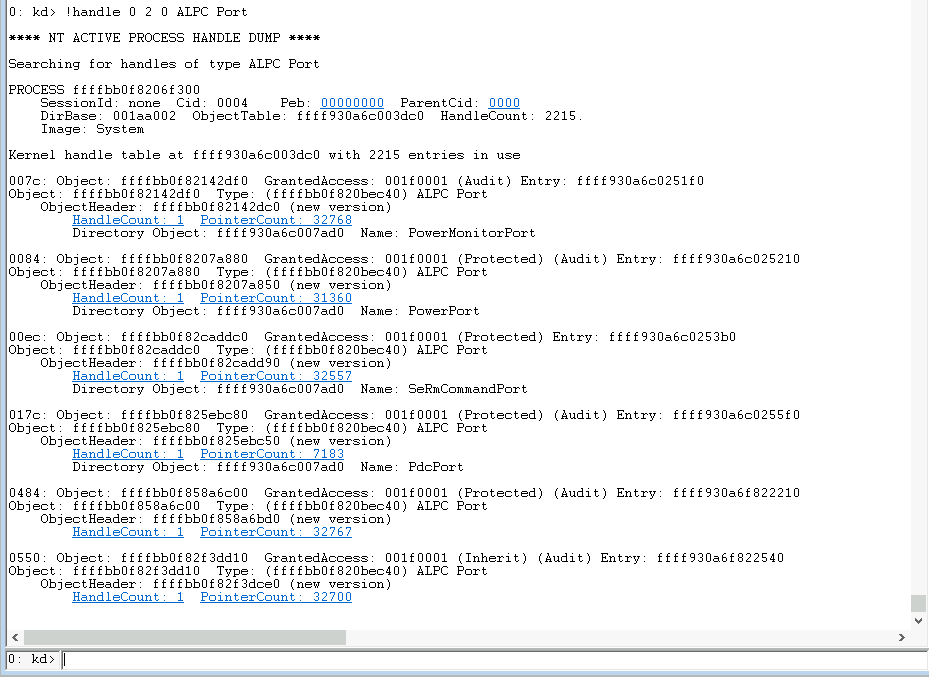

I did not code the 2nd option (parsing the IAT) - if you know a tool that does this let me know, but there is an easy, but very slow way to tackle option number 3 (find ALPC handles in processes) using the following WinDbg command: !handle 0 2 0 ALPC Port

Be aware that this is very slow and will probably take a few hours to complete (I stopped after 10 minutes and only got around 18 handles).

But once again thanks to James Forshaw and his NtApiDotNet there is any easier way to code this yourself and speed up this process, plus we can also get some interesting ALPC stats…

You can find that tool here

Note that this program does not run in kernel land, so I’d expect better results with the WinDbg command, but it does its job to list some ALPC ports used by various processes. By iterating over all processes that we have access to, we can also calculate some basic stats about ALPC usage, as shown above. These numbers are not 100% accurate, but with - on average - around 14 ALPC communication port handles used per process we can definitely conclude that ALPC is used quite frequently within Windows.

Once you identify a process that sounds like an interesting target WinDbg can be used again to dig deeper …

Use Event Tracing For Windows

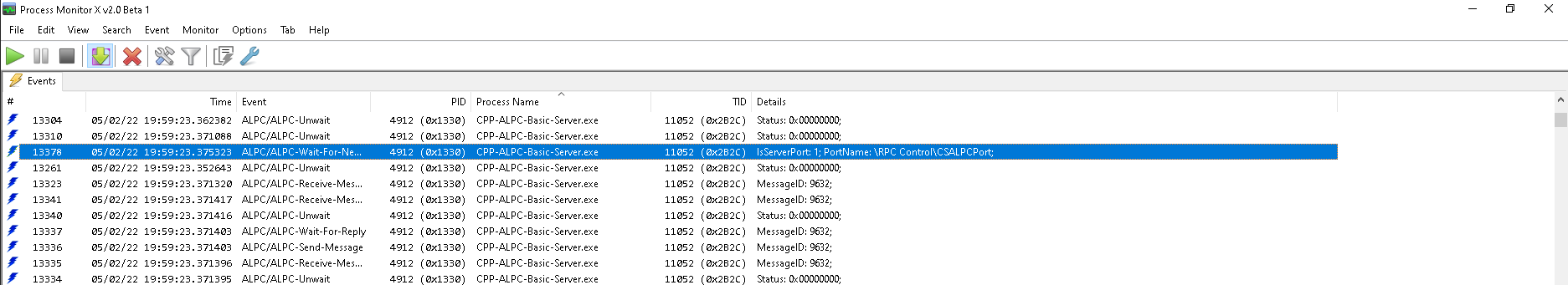

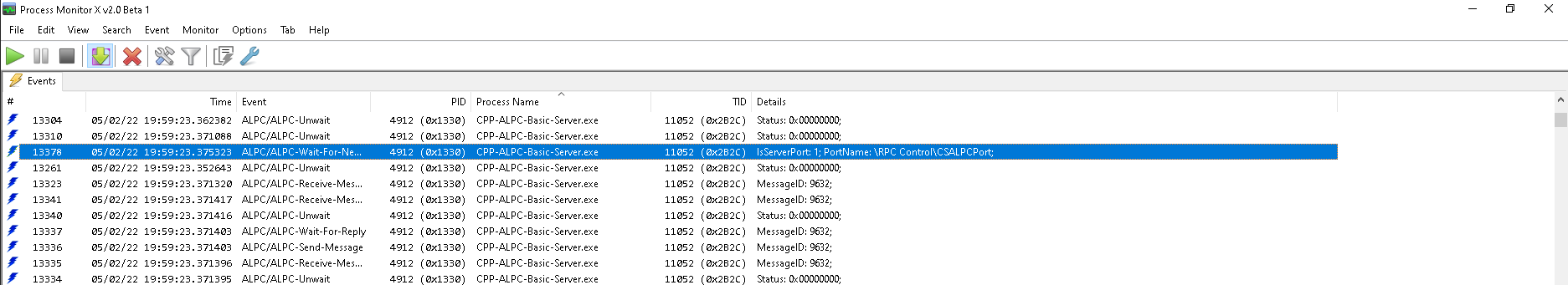

Although ALPC is undocumented a few ALPCs events are exposed as Windows events that can be captured through Event Tracing for Windows (ETW). One of the tools that helps with ALPC events is ProcMonXv2 by zodiacon.

After a few seconds of filtering for the five exposed ALPC events we get over 1000 events, another indication that ALPC is used quite frequently. But apart from that there is not much that ETW can offer in terms of insights into the ALPC communication channels, but anyhow, it did what it was intended to do: Identify ALPC targets.

Impersonation and Non-Impersonation

As with the previous post of the series (see here & here) one interesting attack vector is impersonation of another party.

As last time, I’m not going to cover Impersonation again, but you’ll find all the explanation that you’ll need in the in the Impersonation section of the Named Pipe Post.

For ALPC communication the impersonation routines are bound to messages, which means that both client and server (aka. each communicating party) can impersonate the user on the other side. However, in order to allow for impersonation the impersonated communication partner has to allow to for impersonation to happen AND the impersonating communication partner needs to hold the SeImpersonate privilege (it’s still a secured communication channel, right?)…

Looking at the code there seem to be two options to fulfil the first condition, which is to allow being impersonated:

- The first option: Through the

PortAttributes, e.g. like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

// QOS

SecurityQos.ImpersonationLevel = SecurityImpersonation;

SecurityQos.ContextTrackingMode = SECURITY_STATIC_TRACKING;

SecurityQos.EffectiveOnly = 0;

SecurityQos.Length = sizeof(SecurityQos);

// ALPC Port Attributs

PortAttributes.SecurityQos = SecurityQos;

PortAttributes.Flags = ALPC_PORTFLG_ALLOWIMPERSONATION;

- The second option: Through the

ALPC_MESSAGE_SECURITY_ATTRIBUTEmessage attribute

1

2

3

pMsgAttrSend = setup_sample_message_attributes(hSrvCommPort, NULL, ALPC_MESSAGE_SECURITY_ATTRIBUTE); // setup security attribute

pMsgAttrSend->ValidAttributes |= ALPC_MESSAGE_SECURITY_ATTRIBUTE; // specify it to be valid for the next message

NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort(...) // send the message

If you’re not super familiar with VC++/ALPC code, these snippets might not tell you anything, which is totally fine. The point here is: In theory there are two options to specify that you allow impersonation.

However, there is a catch:

- If the server (the one with the connection port handle) wants to impersonate a client then impersonation is allowed if the client specified EITHER the first option OR the second (or both, but one option is sufficient).

- However if the client wants to impersonate the server, then the server has to provide the 2nd option. In other words: The server has to send the

ALPC_MESSAGE_SECURITY_ATTRIBUTEto allow the client to impersonate the server.

I’ve looked at both routes: A server impersonating a client and a client impersonating a server.

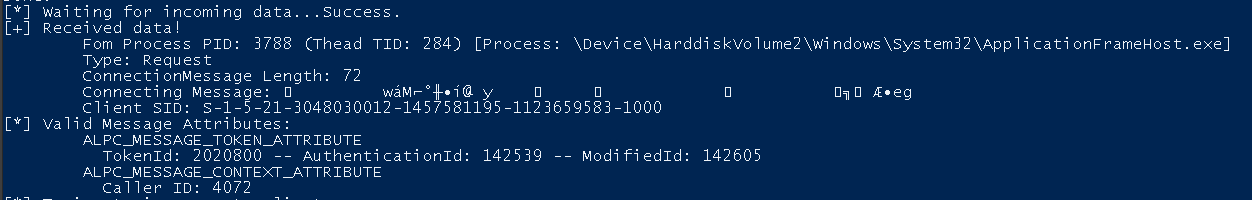

My first path was finding clients attempting to connect to a server port that does not exist in order to check for impersonation conditions. I tried various methods, but so far I haven’t figured a great way to identify such clients. I managed to use breakpoints in the kernel to manually spot some cases, but so far couldn’t find any interesting ones that would allow for client impersonation. Below is an example of the “ApplicationFrameHost.exe” trying to connect to an ALPC port that does not exist, which I could catch with my sample server, however, the process does not allow impersonation (and the application runs as my current user)…

Not a successful impersonation attempt, but at least it proves the idea.

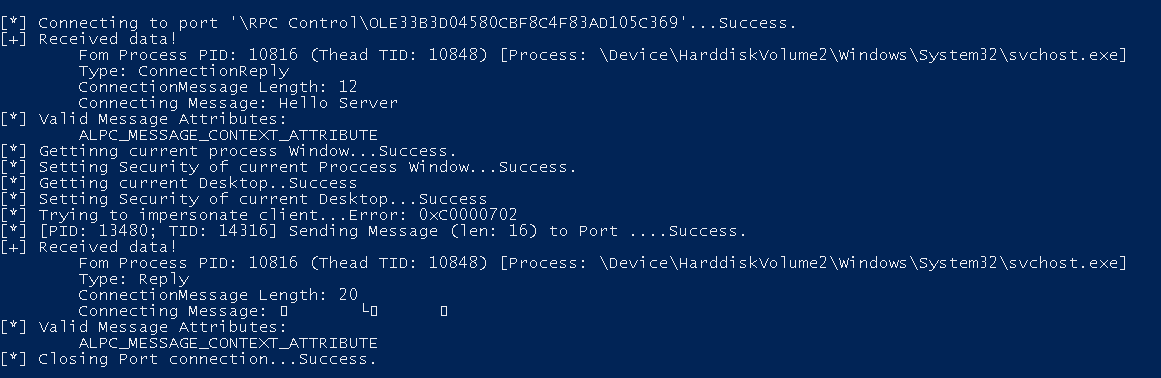

Onto the other path: I located a bunch of ALPC connection ports using Get-AccessibleAlpcPort as shown previously and instructed my ALPC client to connect to these in order to verify whether these a) allow me to connect, b) send me any actual message back and c) send impersonation message attributes along with a message. For all of the ALPC connection ports I checked at best I got some short initialization message with an ALPC_MESSAGE_CONTEXT_ATTRIBUTE back, which is not useful for impersonation, but at least once again it showcases the idea here:

Server Non-Impersonation

In the RPC Part of the series I mentioned that it could also be interesting to connect to a server, that does use impersonation to change the security context of its thread to the security context of the calling client, but does not check if the impersonation succeeds or fails. In such a scenario the server might be tricked into executing tasks with its own - potentially elevated - security context. As detailed in the post about RPC, finding such occasions comes down to a case-by-base analysis of a specific ALPC server process you’re looking at. What you need for this is:

- A server process opening an ALPC port that your client can connect to

- The server has to accept connection messages and must attempt to impersonate the server

- The server must not check if the impersonation succeeds or fails

- (For relevant cases the server must run in a different security context then your client, aka. different user or different integrity level)

As of now I can’t think of a good way of automating or semi-automating the process of finding such targets. The only option that comes to mind is finding ALPC connection ports and reversing the hosting processes.

I’ll get this post updated if I stumble across anything interesting in this direction, but for the main part I wanted to re-iterate the attack path of failed impersonation attempts.

Unfreed Message Objects

As mentioned in the ALPC Message Attributes section there are several message attributes that a client or server can send along with a message. One of these is the ALPC_DATA_VIEW_ATTR attribute that can be used to send information about a mapped view to the other communication party.

To recall: This could for example be used to store larger messages or data in a shared view and send a handle to that shared view to the other party instead of using the double-buffer messaging mechanism to copy data from one memory space into another.

The interesting bit here is that a shared view (or section as its called in Windows) is mapped into the process space of the receiver when being referenced in an ALPC_DATA_VIEW_ATTR attribute. The receiver could then do something with this section (if they are aware of it being mapped), but in the end the receiver of the message has to ensure that a mapped view is freed from its own memory space, and this requires a certain number of steps, which might not be followed correctly. If a receiver fails to free a mapped view, e.g. because it never expected to receive a view in the first place, the sender can send more and more views with arbitrary data to fill the receiver’s memory space with views of arbitrary data, which comes down to a Heap Spray attack.

I only learned about this ALPC attack vector by (once again) listening to Alex Ionescu’s SyScan ALPC Talk and I think there is no way to better phrase and showcase how this attack vector works then he does in this talk, so I’m not going to copy his content and words and just point you to minute 32 of his talk, where he starts to explain the attack. Also you want to see minute 53 of his talk for a demo of his heap spray attack.

The same logics applies with other ALPC message attributes, for example with handles that are send in ALPC_MESSAGE_HANDLE_INFORMATION via the ALPC handle attribute.

Finding vulnerable targets for this type of attacks is - once again - a case-by-case investigative process, where one has to:

- Find processes (of interest) using ALPC communication

- Identify how a target process handles ALPC message attributes and especially if ALPC message attributes are freed

- Get creative about options to abuse non-freed resources, where the obvious PoC option would be to exhaust process memory space

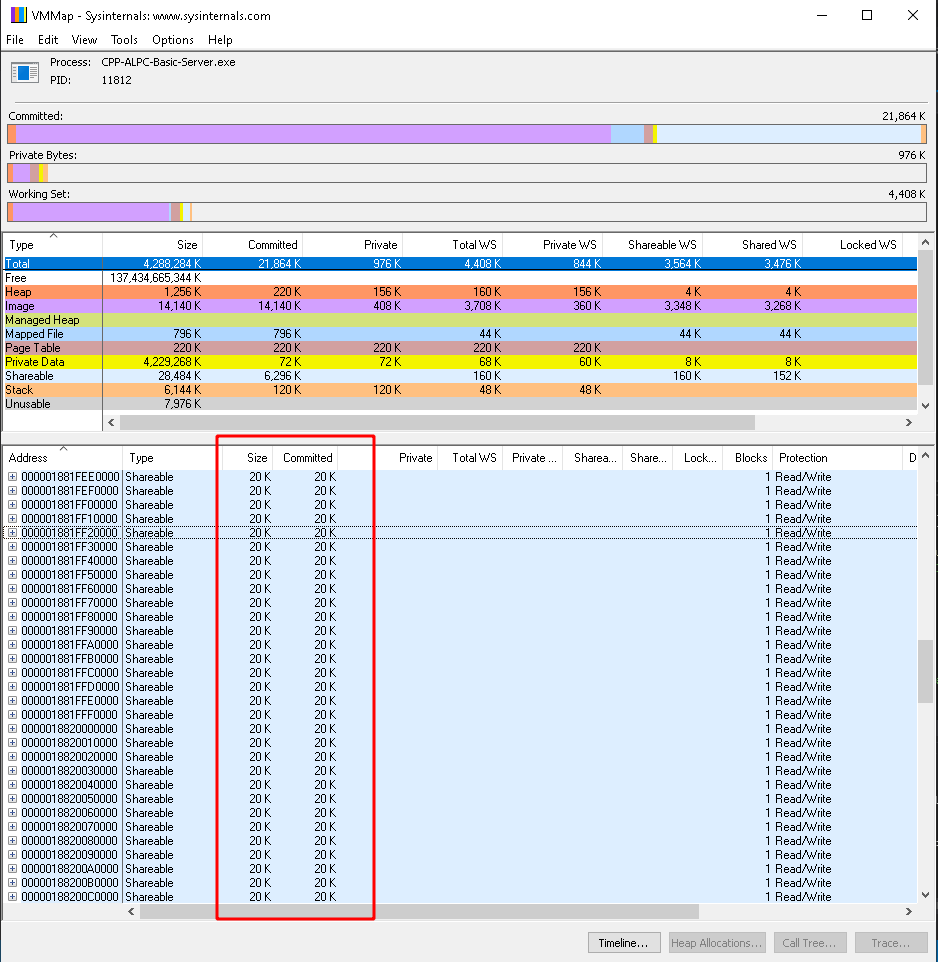

Of course, another valid approach would be to pick a target and just flood it with views (as an example) to check if the result is a lot of shared memory regions being allocated within the target’s address space. A useful tool to inspect the memory regions of a process is VMMap from the Sysinternals suite, which is what I’ve used as a PoC below.

As an example I’ve flooded my ALPC sample server with 20kb views as shown below:

This does work because I did not bother to make any effort to free any allocated attributes in my sample ALPC server.

I’ve also randomly picked a few - like four or five - of Microsoft’s ALPC processes (that I identified using the above shown techniques), but the ones I picked do not seem to make the same mistake.

Honestly, it might be valuable to check more processes for this, but as of know I have no use for this kind of bug other than crashing a process, which - if critical enough - might crash the OS as well (Denial of Service).

Interesting Side note:

In his talk Alex Ionescu mentions that the Windows Memory Manager allocates memory regions on 64kb boundaries, which means that whenever you allocate memory the Memory Manager places this memory at the start of the next available 64kb block. Which allows you, as an attacker, to create and map views of arbitrary size (preferably smaller than 64kb to make the memory exhaustion efficient) and the OS will map the view in the server’s memory and mark 64kb-YourViewSize as unusable memory, because it needs to align all memory allocation to 64kb boundaries. You want to see minute 54 of Alex’s talk to get a visual and verbal explanation of this effect.

Raymond Chen explains the reasoning behind the 64kb granularity here.

At the end of the day memory exhaustion attacks are of course not the only viable option to use a memory/heap spray primitive, which people smarter than me can turn into a exploit path…

Conclusion

ALPC is undocumented and quite complex, but as a motivational benefit: Vulnerabilities inside of ALPC can become very powerful as ALPC is ubiquitous within the Windows OS, all of the built-in high privileged processes use ALPC and due to its communication architecture it is an attractive target even from a sandbox perspective.

There is much more to ALPC than I have covered in this post. Potentially one could write an entire book about ALPC, but I hope to have at least touched the basics to get you started in getting interested in ALPC.

To get a first “Where and how much ALPC is in my PC”-impression I recommend starting ProcMonXv2 (by zodiacon) on your host to see thousands of ALPC events firing in a few seconds.

To continue from there you might find my ALPC client and server code useful to play around with ALPC processes and to identify & exploit vulnerabilities within ALPC. If you find yourself coding and/or investigating ALPC make sure to check out the reference section for input on how others dealt with ALPC.

Finally as a last word and to conclude my recommendation from the beginning: If you feel like you could hear another voice & perspective on ALPC, I highly recommend to grab another beverage and an enjoy the following hour of Alex Ionescu talk about LPC, RPC and ALPC:

Appendix A: The use of connection and communication ports

When looking into ALPC I initially thought that a server listens on its communication port, which it receives when accepting a client connection via NtAlpcConnectPort. This would have made sense, since it’s called communication port. However, listening for incoming messages on the server’s communication port resulted in a blocking call to NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort that never came back with a message.

So my assumption about the server’s ALPC communication port must have been wrong, which puzzled me, since the client on the other side does get messages on his communication port. I hung on this question for a while until I reached out to Alex Ionescu to ask him about this and I learned that my assumption was indeed incorrect, but to be more precise it has become incorrect over time: Alex explained to me that the idea I had (server listens and sends messages on its communication port) was the way that LPC (the predecessor of ALPC) was designed to work. This design however would force you to listen on a growing number of communication ports with each new client the server accepts. Imagine a server has 100 clients talking to it, then the server needs to listen on 100 communication ports to get client messages, which often resulted in creating 100 threads, where each thread would communicate with a different client. This was deemed inefficient and a much more efficient solution was to have a single thread listening (and sending) on the server’s connection port, where all messages are being send to this connection port.

That in turn means: A server accepts a client connection, receives a handle to a client’s communication port, but still uses the server’s connection port handle in calls to NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort in order to send and receive messages from all connected clients.

Does that mean that the server’s communication port is obsolete then (and this was my follow up question to Alex)? His answer, once again, made perfect sense and cleared my understanding of ALPC: A server’s per client communication port is used internally by the OS to tie a message, send by a specific client, to this client’s specific communication port. This allows the OS to tie a special context structure to each client communication port that can be used to identify the client. This special context structure is the PortContext, which can be any arbitrary structure, that can be passed to NtAlpcAcceptConnectPort and which can later be extracted from the any message with the ALPC_CONTEXT_ATTR message attribute.

That means: When a server listens on its connection port it receives messages from all clients, but if it wants to know which client send the message, the server can get the port context structure (through the ALPC_CONTEXT_ATTR message attribute), that it assigned to this client upon accepting the connection, and the OS will fetch that context structure from the internally preserved client communication port.

This far we can conclude that the server’s per-client communication port is still important for the OS and still has its place and role in the ALPC communication structure. That does, however, not answer the question why the server would actually need a handle to each-clients communication port (because the client’s PortContext can be extracted from a message, which is received by using the connection port handle).

The answer here is impersonation. When the server wants to impersonate a client it needs to pass the client’s communication port to NtAlpcImpersonateClientOfPort. The reason for this is that the security context information that are needed to perform the impersonation are bound (if allowed by the client) to the client’s communication port. It would make no sense to attach these information to the connection port, because all clients use this connection port, whereas each client has it own unique communication port for each server.

Therefore: If you want to impersonate your clients you want to keep each client’s communication port handle.

References

Below are a few resources that I found helpful to learn and dig into ALPC.

Reference Projects that make use of ALPC

- https://github.com/microsoft/terminal/blob/main/src/interactivity/onecore/ConIoSrvComm.cpp

- https://github.com/DownWithUp/ALPC-Example

- https://github.com/DynamoRIO/drmemory

- https://github.com/hakril/PythonForWindows

- https://docs.rs/

- https://github.com/googleprojectzero/sandbox-attacksurface-analysis-tools

- https://processhacker.sourceforge.io/doc/ntlpcapi_8h.html

- https://github.com/bnagy/w32

- https://github.com/taviso/ctftool

References to ALPC implementation details

- https://github.com/googleprojectzero/sandbox-attacksurface-analysis-tools/blob/main/NtApiDotNet/NtAlpcNative.cs

- https://processhacker.sourceforge.io/doc/ntlpcapi_8h.html

- https://github.com/hakril/PythonForWindows/blob/master/windows/generated_def/windef.py

Talks about ALPC

- Youtube: SyScan’14 Singapore: All About The Rpc, Lrpc, Alpc, And Lpc In Your Pc By Alex Ionescu

- Slides: SyScan’14 Singapore: All About The Rpc, Lrpc, Alpc, And Lpc In Your Pc By Alex Ionescu

- Youtube: Hack.lu 2017 A view into ALPC-RPC by Clement Rouault and Thomas Imbert

- Slides: ALPC Fuzzing Toolkit

LPC References: