Offensive Windows IPC Internals 1: Named Pipes

Contents:

Introduction

This post marks the start of a series of posts about the internals and interesting bits of various Windows based Inter-Process-Communication (IPC) technology components. Initially this series will cover the following topics:

- Named Pipes

- LPC

- ALPC

- RPC

A few IPC technology components are therefore left out, but I might append this series sometime and include for example some of these:

- Window Messages

- DDE (which is based on Window Messages)

- Windows Sockets

- Mail Slots

Alright so let’s get down to it with Named Pipes…

Although the name might sound a bit odd pipes are a very basic and simple technology to enable communication and share data between two processes, where the term pipe simply describes a section of shared memory used by these two processes.

To term this correctly right from the beginning, the IPC technology we’re speaking about is called ‘pipes’ and there are two types of pipes:

- Named Pipes

- Anonymous Pipes

Most of the time when speaking about pipes you’re likely referring to Named Pipes as these offer the full feature set, where anonymous pipes are mostly used for child-parent communications. This also implies: Pipe communication can be between two processes on the same system (with named and anonymous pipes), but can also be made across machine boundaries (only named pipes can talk across machine boundaries). As Named Pipes are most relevant and support the full feature set, this post will focus only on Named Pipes.

To add some historical background for Named Pipes: Named Pipes originated from the OS/2 times. It’s hart to pin down the exact release date named pipes were introduced to Windows, but at least it can be said that it must have been supported in Windows 3.1 in 1992 - as this support is stated in the Windows/DOS Developer’s Journal Volume 4, so it’s fair to assume named pipes have been added to Windows in the early 1990’s.

Before we dive into the Named Pipe internals, please take note that a few code snippets will follow that are taken from my public Named Pipe Sample Implementation. Whenever you feel you want some more context around the snippets head over to the code repo and review the bigger picture.

Named Pipe Messaging

Alright so let’s break things down to get a hold of Named Pipe internals. When you’ve never heard of Named Pipes before imaging this communication technology like a real, steel pipe - you got a hollow bar with two ends and if you shout something into one end a listener will hear your words on the other end. That’s all a Named Pipe does, it transports information from one end to another.

If you’re a Unix user you sure have used pipes before (as this is not a pure Windows technology) with something like this:

cat file.txt | wc -l. A command that outputs the contents of file.txt, but instead of displaying the output to STDOUT (which could be your terminal window) the output is redirected (“piped”) to the input of your second command wc -l, which thereby counts the lines of your file. That’s an example of an anonymous pipe.

A Windows based Named Pipe is as easily understood as the above example. To enable us to use the full feature set of pipes, we’ll move away from Anonymous Pipes and create a Server and a Client that talk to each other.

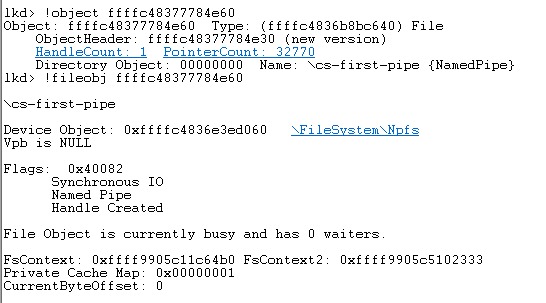

A Named Pipe simply is an Object, more specifically a FILE_OBJECT, that is managed by a special file system, the Named Pipe File System (NPFS):

When you create a Named Pipe, let’s say we call it ‘fpipe’, under the hood you’re creating a FILE_OBJECT with your given name of ‘fpipe’ (hence: named pipe) on a special device drive called ‘pipe’.

Let’s wrap that into a something practical. A named pipe is created by calling the WinAPI function CreateNamedPipe, such as with the below [Source]:

HANDLE serverPipe = CreateNamedPipe(

L"\\\\.\\pipe\\fpipe", // name of our pipe, must be in the form of \\.\pipe\<NAME>

PIPE_ACCESS_DUPLEX, // open mode, specifying a duplex pipe so server and client can send and receive data

PIPE_TYPE_MESSAGE, // MESSAGE mode to send/receive messages in discrete units (instead of a byte stream)

1, // number of instanced for this pipe, 1 is enough for our use case

2048, // output buffer size

2048, // input buffer size

0, // default timeout value, equal to 50 milliseconds

NULL // use default security attributes

);

For now the most interesting part of this call is the \\\\.\\pipe\\fpipe.

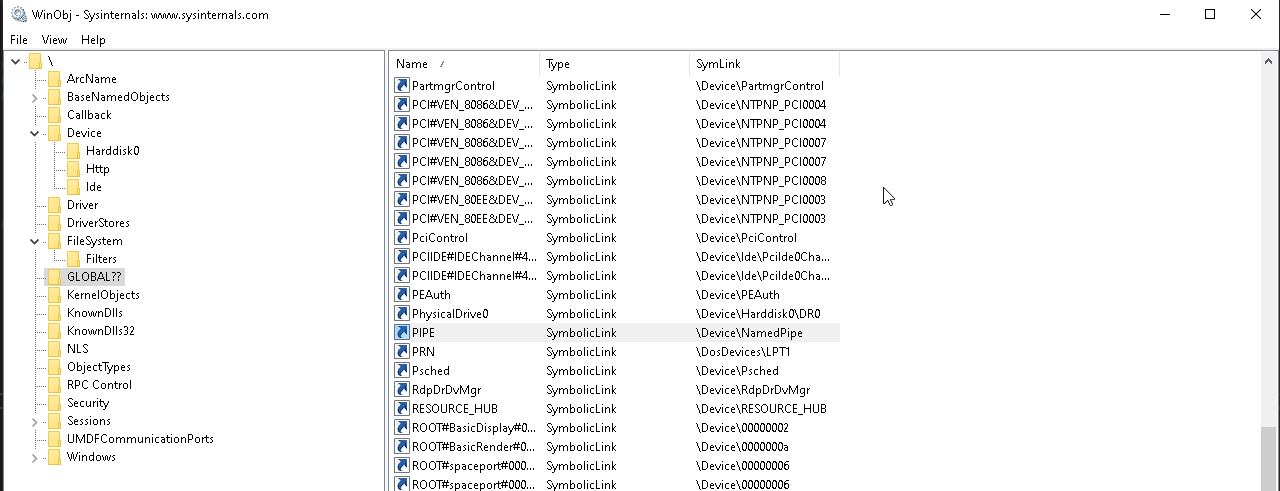

C++ requires escaping of slashes, so language independent this is equal to \\.\pipe\fpipe. The leading ‘\.’ refers to your machines global root directory, where the term ‘pipe’ is a symbolic link to the NamedPipe Device.

Since a Named Pipe Object is a FILE_OBJECT, accessing the named pipe we just created is equal to accessing a “normal” file.

Therefore connecting to a named pipe from a client is therefore as easy as calling CreateFile[Source]:

HANDLE hPipeFile = CreateFile(L"\\\\127.0.0.1\\pipe\\fpipe", GENERIC_READ | GENERIC_WRITE, 0, NULL, OPEN_EXISTING, 0, NULL);

Once connected reading from a pipe just needs a call to ReadFile[Source]:

ReadFile(hPipeFile, pReadBuf, MESSAGE_SIZE, pdwBytesRead, NULL);

Before you can read some data off a pipe, you want your server to write some data to it (which you can read.). That is done by calling - who would have guessed it - WriteFile[Source]:

WriteFile(serverPipe, message, messageLenght, &bytesWritten, NULL);

But what actually happens when you “write” to a pipe?

Once a client connects to your server pipe, the pipe that you created is no longer in a listening state and data can be written to it. The user land call to WriteFile is dispatched to kernel land, where NtWriteFile is called, which determines all the bits and pieces about the Write-Operation, e.g. which device object is associated with the given file, whether or not the Write-Operation should be made synchronous (see section Overlapping Pipe I/O, Blocking mode & In-/Out Buffers), the I/O Request Packet (IRP) is set up and eventually NtWriteFile takes care that your data is written to the file. In our case the specified data is not written to an actual file on disk, but to a shared memory section that is referenced by the file handle return from CreateNamedPipe.

Finally - as mentioned in the introduction - Named Pipes can also be used over a network connection across system boundaries.

There are no additional implementations needed to call a remote Named Pipe server, just make sure that your call to CreateFile specifies an IP or hostname (as with the example above).

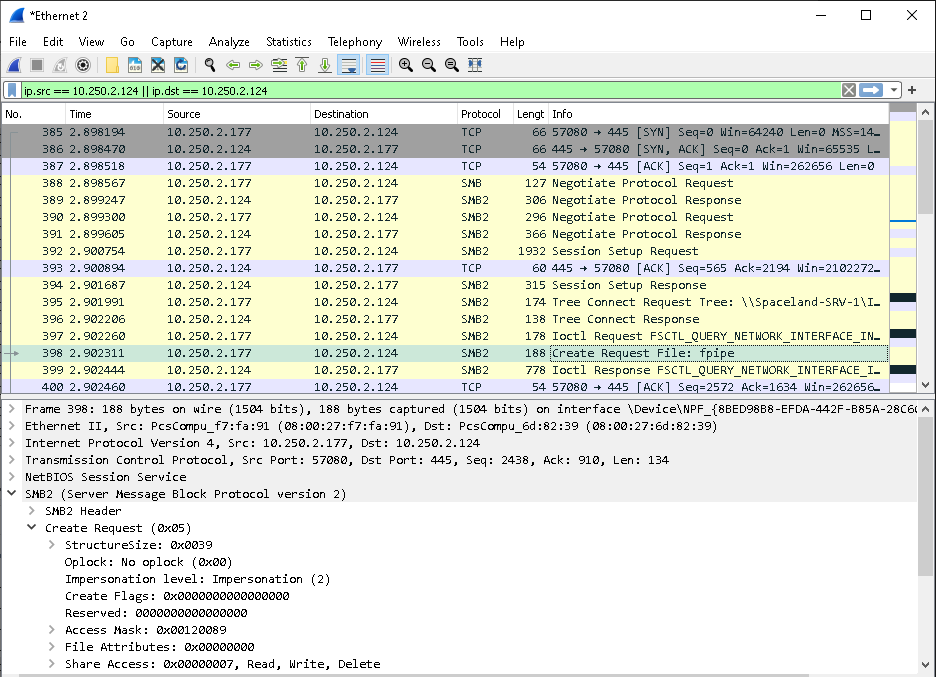

Let’s make a guess: What network protocol will be used when calling a remote pipe server? …. drum rolls … absolutely unsurprising it is SMB.

An SMB connection is made to the remote server, which is by default initialized by a negotiation request to determine the network authentication protocol. Unlike with other IPC mechanisms, such as with RPC, you as a server developer can not control the network authentication protocol as this is always negotiated through SMB. Since Kerberos is the preferred authentication scheme since Windows 2000, Kerberos will be negotiated if possible.

Note: From a client perspective you can effectively choose the authentication protocol by choosing to connect to a hostname or to an IP. Due to the design of Kerberos it cannot handle IPs very well and as such if you choose to connect to an IP address the result of the negotiation will always be NTLM(v2). Whereas when you connect to a hostname you will most likely always end up using Kerberos.

Once the authentication is settled, the actions that client and server want to perform are once again just classic file actions, that are handled by SMB just as any other file operation, e.g. by starting a ‘Create Request File’ request as shown below:

Data Transfer Modes

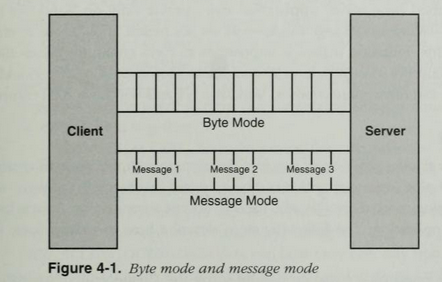

Named pipes offer two basic communication modes: byte mode and message mode.

In byte mode, messages travel as a continuous stream of bytes between the client and the server. This means that a client application and a server application do not know precisely how many bytes are being read from or written to a pipe at any given moment. Therefore a write on one side will not always result in a same-size read on the other. This allows a client and a server to transfer data without caring about the size of the data.

In message mode, the client and the server send and receive data in discrete units. Every time a message is sent on the pipe, it must be read as a complete message. If you read from a server pipe in message mode, but your read buffer is too small to hold all of the data then the portion of data that fits in your buffer will be copied over to it, the remaining data stays in the server’s shared memory section and you’ll get an error 234 (0xEA, ERROR_MORE_DATA) to indicate that there is more data to fetch.

A visual comparison of the messages modes is shown below, taken from “Network programming for Microsoft Windows” (1999):

Overlapping Pipe I/O, Blocking mode & In-/Out Buffers

Overlapping I/O, Blocking mode and In-/Out Buffers are not amazingly important from a security standpoint, but being aware that these exists and what they mean can aid understanding, communication, building and debugging named pipes. Therefore I will add these concepts here briefly.

Overlapping I/O

Several Named Pipe related functions, such as ReadFile, WriteFile, TransactNamedPipe, and ConnectNamedPipe can perform pipe operations either synchronous, meaning the executing thread is waiting for the operation to complete before continuing, or asynchronous, meaning the executing thread fires the action and continues without waiting for its completion.

It’s important to note that asynchronous pipe operations can only be made on a pipe (server) that allows overlapped I/O by setting the FILE_FLAG_OVERLAPPED within the CreateNamedPipe call.

Asynchronous calls can be made either by specifying an OVERLAPPED structure as the last parameter to each of the above mentioned ‘standard’ pipe actions. such as ReadFile, or by specifying a COMPLETION_ROUTINE as the last parameter to the ‘extended’ pipe actions, such as ReadFileEx. The former, OVERLAPPED structure, method is event based, meaning an event object must be created and is signaled once the operation is completed, while the COMPLETION_ROUTINE method is callback based, meaning a callback routine is passed to the executing thread, which is queued and executed once signaled. More details on this can be found here with a sample implementation by Microsoft here.

Blocking mode

The blocking mode behavior is defined when setting up a named pipe server with CreateNamedPipe by using (or omitting) a flag in the dwPipeMode parameter. The following two dwPipeMode flags define the blocking mode of the server:

- PIPE_WAIT (default): Blocking mode enabled. When using named pipe operations, such as ReadFile on a pipe that enabled blocking mode the operation waits for completion. Meaning that a read operation on such a pipe would wait until there is data to read, a write operation would wait until all data is written. This can of course cause an operation to wait indefinitely in some situations.

- PIPE_NOWAIT: Blocking mode disabled. Named pipe operations, such as ReadFile, return immediately. You need routines, such as Overlapping I/O, to ensure all data is read or written.

In-/Out Buffers

By In-/Out Buffers I’m referring to the input and output buffers of the named pipe server that you create when calling CreateNamedPipe and more precisely to the sizes of these buffers in the nInBufferSize and nOutBufferSize parameters.

When performing read and write operations your named pipe server uses non-paged memory (meaning physical memory) to temporarily store data which is to be read or written. An attacker who is allowed to influence these values for a created server can abuse these to potentially cause a system crash by choosing large buffers or to delay pipe operations by choosing a small buffer (e.g. 0):

- Large buffers: As the In-/Out Buffers are non-paged the server will run out of memory if they are chosen too big. However, the nInBufferSize and nOutBufferSize parameters are not ‘blindly’ accepted by the system. The upper limit is defined by a system depended constant; I couldn’t find super accurate information about this constant (and didn’t dig through the headers); This post indicates that it’s ~4GB for an x64 Windows7 system.

- Small buffers: A buffer size of 0 is absolutely valid for nInBufferSize and nOutBufferSize. If the system would strictly enforce what it’s been told you wouldn’t be able to write anything to your pipe, cause a buffer of size 0 is … well, a not existing buffer. Gladly the system is smart enough to understand that you’re asking for a minimum buffer and will therefore expand the actual buffer allocated to the size it receives, but that comes with a consequence to performance. A buffer size of 0 means every byte must be read by the process on the other side of the pipe (and thereby clearing the buffer) before new data can be written to the buffer. This is true for both, the nInBufferSize and nOutBufferSize. A buffer of size 0 could thereby cause server delays.

Named Pipe Security

Once again we can make this chapter about how to set and control the security of a named pipe rather short, but it’s important to be aware how this is done.

The only gear you can turn when you want to secure your named pipe setup is setting a Security Descriptor for the named pipe server as the last parameter (lpSecurityAttributes) to the CreateNamedPipe call.

If you want some background on what a Security Descriptor is, how it’s used and how it could look like you’ll find the answers in my post A Windows Authorization Guide.

Setting this Security Descriptor is optional; A default Security Descriptor can be be set by specifying NULL to the lpSecurityAttributes parameter.

The Windows docs define what the default Security Descriptor does for your named pipe server:

The ACLs in the default security descriptor for a named pipe grant full control to the LocalSystem account, administrators, and the creator owner. They also grant read access to members of the Everyone group and the anonymous account.

Source: CreateNamedPipe > Paremter > lpSecurityAttributes

So by default Everyone can read from your named pipe server if you don’t specify a Security Descriptor, regardless if the reading client is on the same machine or not.

If you connect to a named pipe server without a Security Descriptor set but still get an Access Denied Error (error code: 5) be sure you’ve only specified READ access (note that the example above specifies READ and WRITE access with GENERIC_READ | GENERIC_WRITE).

For remote connections, note once again - as described at the end of the Named Pipe Messaging chapter - that the network authentication protocol is negotiated between the client and server through the SMB protocol. There is no way to programmatically enforce the use of the stronger Kerberos protocol (you only could disable NTLM on the server host).

Impersonation

Impersonation is a simple concept that we’ll need in the following section to talk about attack vectors with named pipes.

If you’re familiar with Impersonation feel free to skip this section; Impersonation is not specific to Named Pipes.

If you’re not yet came across Impersonation in a Windows environment, let me summarize this concept quickly for you:

Impersonation is the ability of a thread to execute in a security context different from the security context of the process that owns the thread. Impersonation typically applies in a Client-Server architecture where a client connects to the server and the server could (if needed) impersonate the client. Impersonation enables the server (thread) to perform actions on behalf of the client, but within the limits of the client’s access rights.

A typical scenario would be a server that wants the access some records (say in database), but only the client is allowed to access its own records. The server could now reply back to the client, asking to fetch the records itself and send these over to the server, or the server could use an authorization protocol to prove the client allowed the server to access the record, or - and this is what Impersonation is - the client sends the server some identification information and allows the server to switch into the role of the client. Somewhat like the client giving its driver license to the server along with the permission to use that license to identify towards other parties, such as a gatekeeper (or more technically a database server).

The identification information, such as the information specifying who the client is (such as the SID) are packed in a structure called a security context. This structure is baked deeply into the internals of the operating system and is a required piece of information for inter process communication. Due to that the client can’t make an IPC call without a security context, but it needs a way to specify what it allows the server to know about and do with its identity. To control that Microsoft created so called Impersonation Levels.

The SECURITY_IMPERSONATION_LEVEL enumeration structure defines four Impersonation Levels that determine the operations a server can perform in the client’s context.

| SECURITY_IMPERSONATION_LEVEL | Description |

|---|---|

| SecurityAnonymous | The server cannot impersonate or identify the client. |

| SecurityIdentification | The server can get the identity and privileges of the client, but cannot impersonate the client. |

| SecurityImpersonation | The server can impersonate the client’s security context on the local system. |

| SecurityDelegation | The server can impersonate the client’s security context on remote systems. |

For more background information on Impersonation have a read through Microsoft’s docs for Client Impersonation.

For some context around Impersonation have a look at the Access Tokens and the following Impersonation section in my post about Windows Authorization.

Impersonating a Named Pipe Client

Okay, so while we’re on the topic and in case you’re not totally bored yet. Let’s have a quick run down of what actually happens under the hood if a server impersonated a client.

If you’re more interested in how to implement this, you’ll find the answer in my sample implementation here.

- Step 1: The server waits for an incoming connection from a client and afterwards calls the ImpersonateNamedPipeClient function.

- Step 2: This call results in a call to NtCreateEvent (to create a callback event) and to NtFsControlFile, which is the function executing the impersonation.

- Step 3: NtFsControlFile is a general purpose function where its action is specified by an argument, which in this case is FSCTL_PIPE_Impersonate.

The below is based on the open source code of ReactOS, but i think it’s fair to assume the Windows Kernel Team implemented it in a similar way. - Step 4: Further down the call stack NpCommonFileSystemControl is called where FSCTL_PIPE_IMPERSONATE is passed as an argument and used in a switch-case instruction to determine what to do.

- Step 5: NpCommonFileSystemControl calls NbAcquireExeclusiveVcb to lock an object and NpImpersonate is called given the server’s pipe object and the IRP (I/O Request Object) issued by the client.

- Step 6: NpImpersonate then in turn calls SeImpersonateClientEx with the client’s security context, which has been obtained from the client’s IRP, as a parameter.

- Step 7: SeImpersonateClientEx in turn calls PsImpersonateClient with the server’s thread object and the client’s security token, which is extracted from the client’s security context

- Step 8: The server’s thread context is then changed to the client’s security context.

- Step 9: Any action the server takes and any function the server calls while in the security context of the client are made with the identify of the client and thereby impersonating the client.

- Step 10: If the server is done with what it intended to do while being the client, the server calls RevertToSelf to switch back to its own, original thread context.

Attack Surface

Client Impersonation

Sooo finally we’re talking about attack surface. The most important attack vector based on named pipes is Impersonation.

Luckily we’ve introduced and understood the concept of Impersonation already in the above section, so we can dive right in.

Attack scenario

Impersonation with named pipes can best be abused when you got a service, program or routine that allows you to specify or control to access a file (doesn’t matter if it allows you READ or WRITE access or both). Due to the fact that Named Pipes are basically FILE_OBJECTs and operate on the same access functions as regular files (ReadFile, WriteFile, CreateFile, …) you can specify a named pipe instead of a regular file name and make your victim process connect to a named pipe under your control.

Prerequisites

There are two important aspects you need to check when attempting to impersonate a client.

The first is to check how the client implements the file access, more specifically does the client specify the SECURITY_SQOS_PRESENT flag when calling CreateFile ?

A vulnerable call to CreateFile looks like this:

hFile = CreateFile(pipeName, GENERIC_READ, 0, NULL, OPEN_EXISTING, 0, NULL);

Whereas a safe call to CreateFile like this:

// calling with explicit SECURITY_IMPERSONATION_LEVEL

hFile = CreateFile(pipeName, GENERIC_READ, 0, NULL, OPEN_EXISTING, SECURITY_SQOS_PRESENT | SECURITY_IDENTIFICATION , NULL);

// calling without explicit SECURITY_IMPERSONATION_LEVEL

hFile = CreateFile(pipeName, GENERIC_READ, 0, NULL, OPEN_EXISTING, SECURITY_SQOS_PRESENT, NULL);

By default a call without explicitly specifying the SECURITY_IMPERSONATION_LEVEL (as with the later example above) is made with the Impersonation Level of SecurityAnonymous.

If the SECURITY_SQOS_PRESENT flag is set without any additional Impersonation Level (IL) or with an IL set to SECURITY_IDENTIFICATION or SECURITY_ANONYMOUS you cannot impersonate the client.

The second important aspect to check is the file name, aka. the lpFileName parameter, given to CreateFile. There is an important distinction between calling local named pipes or calling remote named pipes.

A call to a local named pipe is defined by the file location \\.\pipe\<SomeName>.

Calls to local pipes can only be impersonated when the SECURITY_SQOS_PRESENT flag is explicitly set with an Impersonation Level above SECURITY_IDENTIFICATION. Therefore a vulnerable call looks like this:

hFile = CreateFile(L"\\.\pipe\fpipe", GENERIC_READ, 0, NULL, OPEN_EXISTING, SECURITY_SQOS_PRESENT | SECURITY_IMPERSONATION, NULL);

To be clear. A safe call to a local pipe would look like this:

hFile = CreateFile(L"\\.\pipe\fpipe", GENERIC_READ, 0, NULL, OPEN_EXISTING, 0, NULL);

This later call is safe even without the SECURITY_SQOS_PRESENT, because a local pipe is called.

A remote named pipe on the other hand is defined by a lpFileName beginning with a hostname or an IP, such as: \\ServerA.domain.local\pipe\<SomeName>.

Now comes the important bit:

When the SECURITY_SQOS_PRESENT flag is not present and a remote named pipe is called the impersonation level is defined by the user privileges running the name pipe server.

That means that when you call a remote named pipe without the SECURITY_SQOS_PRESENT flag, your attacker user that runs the pipe must hold the SeImpersonatePrivilege (SE_IMPERSONATE_NAME) in order to impersonate the client.

If your user does not hold this privilege the Impersonation Level will be set to SecurityIdentification (which allows you to identify, but not impersonate the user).

But that also means that if your user holds the SeEnableDelegationPrivilege (SE_ENABLE_DELEGATION_NAME), the Impersonation Level is set to SecurityDelegation and you can even authenticate the victim user against other network services.

An important take away here is:

You can make a remote pipe call to a named pipe running on the same machine by specifying

\\127.0.0.1\pipe\<SomeName>

To finally bring the pieces together:

- If the SECURITY_SQOS_PRESENT is not set you can impersonate a client if you have a user with at least SE_IMPERSONATE_NAME privileges, but for named pipes running on the same machine you need to call them via

\\127.0.0.1\pipe\... - If the SECURITY_SQOS_PRESENT is set you can only impersonate a client if an Impersonation Level above SECURITY_IDENTIFICATION is set along with it (regardless if you call a named pipe locally or remote).

Misleading Documentation

Microsoft’s documentation about Impersonation Levels (Authorization) states the following:

When the named pipe, RPC, or DDE connection is remote, the flags passed to CreateFile to set the impersonation level are ignored. In this case, the impersonation level of the client is determined by the impersonation levels enabled by the server, which is set by a flag on the server’s account in the directory service. For example, if the server is enabled for delegation, the client’s impersonation level will also be set to delegation even if the flags passed to CreateFile specify the identification impersonation level.

Source: Windows Docs: Impersonation Levels (Authorization)

Be aware here that this is technically true, but it’s somewhat misleading…

The accurate version is: When calling a remote named pipe and you only specify Impersonation Level flags (and nothing else) to CreateFile then these will be ignore, but if you specify Impersonation Flags alongside with the SECURITY_SQOS_PRESENT flag, then these will be respected.

Examples:

// In the below call the SECURITY_IDENTIFICATION flag will be respected by the remote server

hFile = CreateFile(L"\\ServerA.domain.local", GENERIC_READ, 0, NULL, OPEN_EXISTING, SECURITY_SQOS_PRESENT | SECURITY_IDENTIFICATION, NULL);

/* --> The server will obtain a SECURITY_IDENTIFICATION token */

// In this call the SECURITY_IDENTIFICATION flag will be ignored

hFile = CreateFile(L"\\ServerA.domain.local", GENERIC_READ, 0, NULL, OPEN_EXISTING, SECURITY_IDENTIFICATION, NULL);

/* --> The server will obtain a token based on the privileges of the user running the server.

A user holding SeImpersonatePrivilege will get an SECURITY_IMPERSONATION token */

// In this call the Impersonation Level will default to SECURITY_ANONYMOUS and will be respected

hFile = CreateFile(L"\\ServerA.domain.local", GENERIC_READ, 0, NULL, OPEN_EXISTING, SECURITY_SQOS_PRESENT, NULL);

/* --> The server will obtain a SECURITY_ANONYMOUS token. A call to OpenThreadToken will result in error 1347 (0x543, ERROR_CANT_OPEN_ANONYMOUS)*/

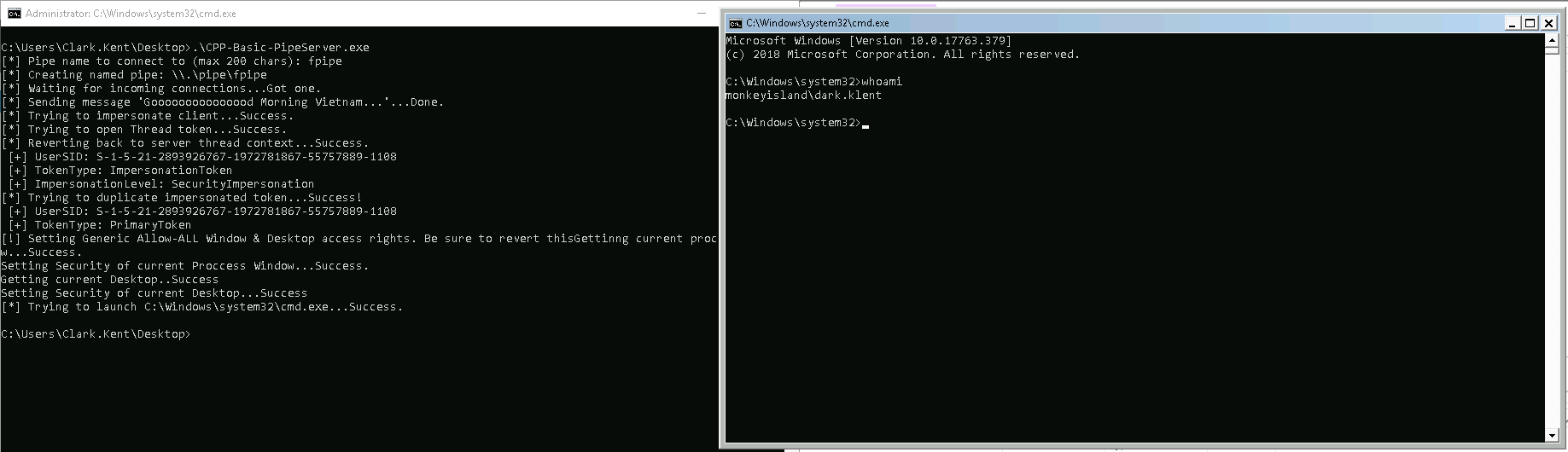

Implementation

You can find an a full implementation in my sample code here. A quick run down of the implementation is shown below:

// Create a server named pipe

serverPipe = CreateNamedPipe(

pipeName, // name of our pipe, must be in the form of \\.\pipe\<NAME>

PIPE_ACCESS_DUPLEX, // The rest of the parameters don't really matter

PIPE_TYPE_MESSAGE, // as all you want is impersonate the client...

1, //

2048, //

2048, //

0, //

NULL // This should ne NULL so every client can connect

);

// wait for pipe connections

BOOL bPipeConnected = ConnectNamedPipe(serverPipe, NULL);

// Impersonate client

BOOL bImpersonated = ImpersonateNamedPipeClient(serverPipe);

// if successful open Thread token - your current thread token is now the client's token

BOOL bSuccess = OpenThreadToken(GetCurrentThread(), TOKEN_ALL_ACCESS, FALSE, &hToken);

// now you got the client token saved in hToken and you can safeyl revert back to self

bSuccess = RevertToSelf();

// Now duplicate the client's token to get a Primary token

bSuccess = DuplicateTokenEx(hToken,

TOKEN_ALL_ACCESS,

NULL,

SecurityImpersonation,

TokenPrimary,

&hDuppedToken

);

// If that succeeds you got a Primary token as hDuppedToken and you can create a proccess with that token

CreateProcessWithTokenW(hDuppedToken, LOGON_WITH_PROFILE, command, NULL, CREATE_NEW_CONSOLE, NULL, NULL, &si, &pi);

The result can be seen below:

There are some catches when you implement this on your own:

- When you create a process with CreateProcessWithTokenW, you need to RevertToSelf before calling CreateProcessWithTokenW otherwise you’ll receive an error.

- When you want to create a window based process (something with a window that pops up, such as calc.exe or cmd.exe) you need to grant the client access to your Window and Desktop. A sample implementation allowing all users to access to your Window and Desktop can be found here.

Instance Creation Race Condition

Named Pipes instances are created and live within a global ‘namespace’ (actually technically there is no namespace, but this aids understanding that all named pipes live under to same roof) within the Name Pipe File System (NPFS) device drive. Moreover multiple named pipes with the same name can exist under this one roof.

So what happens if an application creates a named pipe that already exists? Well if you don’t set the right flags nothing happens, meaning you won’t get an error and even worse you won’t get client connections, due to the fact that Named Pipe instances are organized in a FIFO (First In First Out) stack.

This design makes Named Pipes vulnerable for instance creation race condition vulnerabilities.

Attack scenario

The attack scenario to exploit such a race condition is as follows: You’ve identified a service, program or routine that creates a named pipe that is used by client applications running in a different security context (let’s say they run under the NT Service user). The server creates a named pipe for communication with the client application(s). Once in a while a client connects to the server’s named pipe - it wouldn’t be uncommon if the server application triggers the clients to connect after the server pipe is created. You figure out when and how the server is started and the name of the pipe it creates.

Now you’re writing a program that creates a named pipe with the same name in a scenario where your named pipe instance is created before the target server’s named pipe. If the server’s named pipe is created insecurely it will not notice that a named pipe with the same name already exist and will trigger the clients to connect. Due to the FIFO stack the clients will connect to you and you can read or write their data or try to impersonate the clients.

Prerequisites

For this attack to work you need a target server that doesn’t check if a named pipe with the same name already exists. Usually a server doesn’t have extra code to check manually if a pipe with the same name already exists - thinking about it you would expect to get an error if your pipe name already exists right? But that doesn’t happen because two named pipe instances with the same name are absolutely valid … for whatever reason.

But to counter this attack Microsoft has added the FILE_FLAG_FIRST_PIPE_INSTANCE flag that can be specified when creating your named pipe through CreateNamedPipe. When this flag is set your create call will return an INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE, which will cause an error in a subsequent call to ConnectNamedPipe.

If you’re target server does not specify the FILE_FLAG_FIRST_PIPE_INSTANCE flag it is likely vulnerable, however there is one additional thing you need to be aware of on the attacker side. When creating a named pipe through CreateNamedPipe there is a nMaxInstances parameter, which specifies…:

The maximum number of instances that can be created for this pipe. The first instance of the pipe can specify this value;

Source: CreateNamedPipe

So if you set this to ‘1’ (as in the sample code above) you kill your own attack vector. To exploit an instance creation race condition vulnerability set this to PIPE_UNLIMITED_INSTANCES.

Implementation

All you need to do for exploitation is create a named pipe instance with the right name at the right time.

My sample implementation here can be used as an implementation template. Throw this in you favorite IDE, set in your pipe name, ensure your named pipe is created with the PIPE_UNLIMITED_INSTANCES flag and fire away.

Instance Creation Special Flavors

Unanswered Pipe Connections

Unanswered pipe connections are those connection attempts issued by clients that - who would have guessed it - are not successful, hence unanswered, because the pipe that is requested by the client is not existing.

The exploit potential here is quite clear and simple: If a client wants to connect to a pipe that’s not existing, we create a pipe that the client can connect to and attempt to manipulate the client with malicious communication or impersonate the client to gain additional privileges.

This vulnerability is sometimes also referred to as superfluous pipe connections (but in my mind that’s not the best terminology for it).

The real question here is: How do we find such clients?

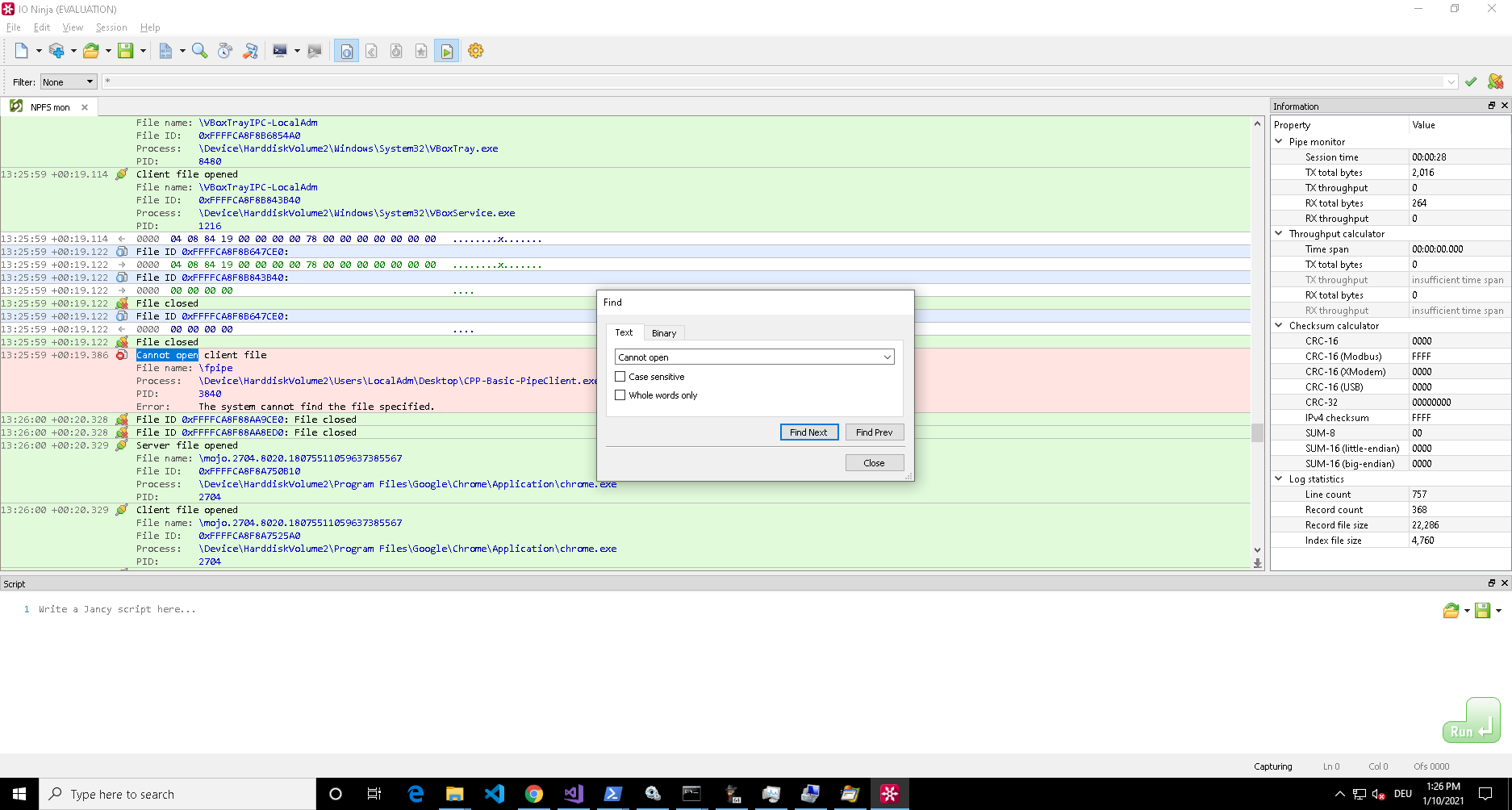

My initial immediate answer would have been: Fire up Procmon and search for failed

CreateFile system calls. But I tested this and it turns out Procmon does not list these calls for pipes… maybe that is because the tool is only inspecting/listening on file operations through the NTFS driver, but i haven’t looked any deeper into this (maybe there is a trick/switch i didn’t know) - I’ll update if I stumble across the answer…

Another option is the Pipe Monitor of the IO Ninja toolset. This tool requires a license, but offers a free trial period to play around with it. The Pipe Monitor offers functionality to inspect pipe activity on the system and comes with a few basic filters for processes, file names and such. As you want to search for all processes and all file names I filtered for ‘*’, let it run and used the search function to look for ‘Cannot open’:

If you know any other way to do this using open source tooling, let me know (/ 0xcsandker) ;)

Killing Pipe Servers

If you can’t find unanswered pipe connection attempts, but identified an interesting pipe client, that you’d like to talk to or impersonate, another option to get the client’s connection is to kill its current pipe server.

In the Instance Creation Race Condition section I’ve described that you can have multiple named pipes with the same name in the same ‘namespace’.

If your target server didn’t set the nMaxInstances parameter to ‘1’, you can create a second named pipe server with the same name and place yourself in the queue to serve clients. You will not receive any client calls as long as the original pipe server is serving, so the idea for this attack is to disrupt or kill the original pipe server to step in with your malicious server.

When it comes to killing or disrupting the original pipe server I can’t assist with any general purpose prerequisites or implementations, because this always depends on who is running the target server and on your access rights and user privileges.

When analyzing your target server for kill techniques try to think outside the box, there is more than just sending a shutdown signal to a process, e.g. there could be error conditions that cause the server to shutdown or restart (remember you’re number 2 in the queue - a restart might be enough to get in position).

Also note that a pipe server is just an instance running on a virtual FILE_OBJECT, therefore all named pipe servers will be terminated once their handle reference count reaches 0. A handle is for example opened by a client connecting to it. So a server could also be killed by killing all its handles (of course you only gain something if the clients come back to you after loosing connection).

PeekNamedPipe

There might be scenarios where you’re interested in the data that is exchanged rather than in manipulating or impersonating pipe clients.

Due to the fact that all named pipe instances live under the same roof, aka. in the same global ‘namespace’ aka. on the same virtual NPFS device drive (as briefly mentioned before) there is no system barrier that stops you from connecting to any arbitrary (SYSTEM or non-SYSTEM) named pipe instance and have a look at the data in the pipe (technically ‘in the pipe’ means within the shared memory section allocated by the pipe server).

Prerequisites

As mentioned in the section Named Pipe Security the only gear you can turn when securing your named pipe is using a Security Descriptor as the last parameter (lpSecurityAttributes) to the CreateNamedPipe call. And that’s all that would prevent you from accessing any arbitrary named pipe instance. So all you need to check for when searching for a target is if this parameter is set and secured to prevent unauthorized access.

If you need some background on Security Descriptors and what to look for (the ACLs in the DACL) check out my post: A Windows Authorization Guide

Implementation

When you found a suitable target there is one more thing you need to keep in mind: If you’re reading from a named pipe by using ReadFile, you’re removing the data from the server’s shared memory and the next, potentially legitimate client, who attempts to read from the pipe will not find any data and potentially raise an error.

But you can use the PeekNamedPipe function to view the data without removing it from shared memory.

An implementation snippet based on the my sample code could look like this:

// all the vars you need

const int MESSAGE_SIZE = 512;

BOOL bSuccess;

LPCWSTR pipeName = L"\\\\.\\pipe\\fpipe";

HANDLE hFile = NULL;

LPWSTR pReadBuf[MESSAGE_SIZE] = { 0 };

LPDWORD pdwBytesRead = { 0 };

LPDWORD pTotalBytesAvail = { 0 };

LPDWORD pBytesLeftThisMessage = { 0 };

// connect to named pipe

hFile = CreateFile(pipeName, GENERIC_READ, 0, NULL, OPEN_EXISTING, SECURITY_SQOS_PRESENT | SECURITY_ANONYMOUS, NULL);

// sneak peek data

bSuccess = PeekNamedPipe(

hFile,

pReadBuf,

MESSAGE_SIZE,

pdwBytesRead,

pTotalBytesAvail,

pBytesLeftThisMessage

);

References

That’s about it, if you want to continue to dig into Named Pipes here are some good references to start with:

- Microsoft’s Docs about pipes at https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/ipc/pipes

- Blake Watts paper about Named Pipe Security at http://www.blakewatts.com/namedpipepaper.html

- My Sample C++ Implementation at https://github.com/csandker/InterProcessCommunication-Samples/tree/master/NamedPipes/CPP-NamedPipe-Basic-Client-Server

The Series: Part 2

Part 2 of the series, covering RPC can be found here: Offensive Windows IPC Internals 2: RPC